The Italian language has its native seat and living source in Middle Italy, or more precisely Tuscany and indeed Florence. For real linguistic unity is far from existing in Italy; in some respects the variety is less, in others more observable than in other countries which equally boast a political and literary unity. Thus, for example, Italy affords no linguistic contrast so violent as that presented by Great Britain with its English dialects alongside of the Celtic dialects of Ireland, Scotland and Wales, or by France with the French dialects alongside of the Celtic dialects of Brittany, not to speak of the Basque of the Pyrenees and other heterogeneous elements. The presence of not a few Slavs stretching into the district of Udine (Friuli), of Albanian, Greek and Slav settlers in the southern provinces, with the Catalans of Alghero (Sardinia, v. Arch. glott. ix. 261 et seq.), a few Germans at Monte Rosa and in some corners of Venetia, and a remnant or two of other comparatively modern immigrations is not sufficient to produce any such strong contrast in the conditions of the national speech. But, on the other hand, the Neo-Latin dialects which live on side by side in Italy differ from each other much more markedly than, for example, the English dialects or the Spanish; and it must be added that, in Upper Italy especially, the familiar use of the dialects is tenaciously retained even by the most cultivated classes of the population.

In the present rapid sketch of the forms of speech which occur in modern Italy, before considering the Tuscan or Italian par excellence, the language which has come to be the noble organ of modern national culture, it will be convenient to discuss (A) dialects connected in a greater or less degree with Neo-Latin systems that are not peculiar to Italy;[3] (B) dialects which are detached from the true and proper Italian system, but form no integral part of any foreign Neo-Latin system; and (C) dialects which diverge more or less from the true Italian and Tuscan type, but which at the same time can be conjoined with the Tuscan as forming part of a special system of Neo-Latin dialects.

A. Dialects which depend in a greater or less degree on Neo-Latin systems not peculiar to Italy.

1. Franco-Provençal and Provençal Dialects.—(a) Franco-Provençal (see Ascoli, Arch. glott. iii. 61-120; Suchier, in Grundriss der romanischen Philologie, 2nd ed., i. 755, &c.; Nigra, Arch. glott. iii. 1 sqq.; Salvioni, Rendic. istit. lomb., s. ii. vol. xxxvii. 1043 sqq.; Cerlogne, Dictionnaire du patois valdôtain (Aosta, 1907). These occupy at the present time very limited areas at the extreme north-west of the kingdom of Italy. The system stretches from the borders of Savoy and Valais into the upper basin of the Dora Baltea and into the head-valleys of the Orco, of the northern Stura, and of the Dora Riparia. As this portion is cut off by the Alps from the rest of the system, the type is badly preserved; in the valleys of the Stura and the Dora Riparia, indeed, it is passing away and everywhere yielding to the Piedmontese. The most salient characteristic of the Franco-Provençal is the phonetic phenomenon by which the Latin a, whether as an accented or as an unaccented final, is reduced to a thin vowel (ḛ, i) when it follows a sound which is or has been palatal, but on the contrary is kept intact when it follows a sound of another sort. The following are examples from the Italian side of these Alps: Aosta: travaljí, Fr. travailler; zarźí, Fr. charger; enteruźí, Fr. interroger; zḛvra, Fr. chèvre; zir, Fr. cher; gljáçḛ, Fr. glace; vázze, Fr. vache; alongside of sa, Fr. sel; maṅ, Fr. main; epóusa, Fr. épouse; erba, Fr. herbe. Val. Soana: taljér, Fr. tailler; coćí-sse, Fr. se coucher; ćiṅ, Fr. chien; ćívra, Fr. chèvre; vaćći, Fr. vache; mánģi, Fr. manche; alongside of alár, Fr. aller; porta, Fr. porté; amára, Fr. amère; néva, Fr. neuve. Chiamorio (Val di Lanzo): la spranssi dla vendeta, sperantia de illa vindicta. Viù: pansci, pancia. Usseglio: la müragli, muraille. A morphological characteristic is the preservation of that paradigm which is legitimately traced back to the Latin pluperfect indicative, although possibly it may arise from a fusion of this pluperfect with the imperfect subjunctive (amaram, amarem, alongside of habueram, haberem), having in Franco-Provençal as well as in Provençal and in the continental Italian dialects in which it will be met with further on (C. 3, b; cf. B. 2) the function of the conditional. Val Soana: portáro, portáre, portáret; portáront; Aosta: ávre = Prov. agra, haberet (see Arch. iii. 31 n). The final t in the third persons of this paradigm in the Val Soana dialect is, or was, constant in the whole conjugation, and becomes in its turn a particular characteristic in this section of the Franco-Provençal. Val Soana: éret, Lat. erat; sejt, sit; pórtet, portávet; portǫnt, portávǫnt; Chiamorio: jéret, erat; ant dit, habent dictum; èjssount fêt, habuissent factum; Viu: che s’mínget, Ital. che si mangi: Gravere (Val di Susa): at pensá, ha pensato; avát, habebat; Giaglione (sources of the Dora Riparia); maciávont, mangiavano.—From the valleys, where, as has just been said, the type is disappearing, a few examples of what is still genuine Franco-Provençal may be subjoined: Ćivreri (the name of a mountain between the Stura and the Dora Riparia), which, according to the regular course of evolution, presupposes a Latin Capraria (cf. maneri, maniera, even in the Chiamorio dialect); ćarastí (ciarastì), carestia, in the Viu dialect; and ćintá, cantare, in that of Usseglio. From Chiamorio, li téns, i tempi, and chejches birbes, alcune (qualche) birbe, are worthy of mention on account of the final s. [In this connexion should also be mentioned the Franco-Provençal colonies of Transalpine origin, Faeto and Celle, in Apulia (v. Morosi, Archivio glottologico, xii. 33-75), the linguistic relations of which are clearly shown by such examples as talíj, Ital. tagliare; bañíj, Ital. bagnare; side by side with ćantǡ, Ital. cantare; luǡ, Ital. levare.]

(b) Provençal (see La Lettura i. 716-717, Romanische Forschungen xxiii. 525-539).—Farther south, but still in the same western extremity of Piedmont, phenomena continuous with those of the Maritime Alps supply the means of passing from the Franco-Provençal to the Provençal proper, precisely as the same transition takes place beyond the Cottian Alps in Dauphiné almost in the same latitude. On the Italian side of the Cottian and the Maritime Alps the Franco-Provençal and the Provençal are connected with each other by the continuity of the phenomenon ć (a pure explosive) from the Latin c before a. At Oulx (sources of the Dora Riparia), which seems, however, to have a rather mixed dialect, there also occurs the important Franco-Provençal phenomenon of the surd interdental (English th in thief) instead of the surd sibilant (for example ithí = Fr. ici). At the same time agü = avuto, takes us to the Provençal. [If, in addition to the Provençal characteristic of which agǘ is an example, we consider those characteristics also Provençal, such as the o for a final unaccented, the preservation of the Latin diphthong au, p between vowels preserved as b, we shall find that they occur, together or separately, in all the Alpine varieties of Piedmont, from the upper valleys of the Dora Riparia and Clusone to the Colle di Tenda. Thus at Fenestrelle (upper valley of the Clusone): agü, vengü, Ital. venuto; pauc, Lat. paucu, Ital. poco; aribá (Lat. rīpa), Ital. arrivare; trubá, Ital. trovare; ciabrin, Ital. capretto; at Oulx (source of the Dora Riparia): agü, vengü; üno gran famino è venüo, Ital. una gran fame è venuta; at Giaglione: auvou, Ital. odo (Lat. audio); arribá, resebü, Ital. ricevuto (Lat. recipere); at Oncino (source of the Po): agü, vengü; ero en campagno, Ital. “era in campagna”; donavo, Ital. dava; paure, Lat. pauper, Ital. povero; trubá, ciabrí; at Sanpeyre (valley of the Varaita): agü, volgü, Ital. voluto; pressioso, Ital. preziosa; fasio, Ital. faceva; trobar; at Acceglio (valley of the Macra): venghess, Ital. venisse; virro, Ital. ghiera; chesto allegrio, Ital. questa allegria; ero, Ital. era; trobá; at Castelmagno (valley of the Grana): gü, vengü; rabbio, Ital. rabbia; trubar; at Vinadio (valley of the southern Stura); agü, beigü, Ital. bevuto; cadëno, Ital. catena; mangģo, Ital. manica; ćanto, Ital. canta; pau, auvì, Ital. udito; šabe, Ital. sapete; trobar; at Valdieri and Roaschia (valley of the Gesso): purgü, Ital. potuto; pjagü, Ital. piaciuto; corrogǘ, Ital. corso; pau; arribá, ciabri; at Limone (Colle di Tenda): agü, vengü; saber, Ital. sapere; arübá, trubava. Provençal also, though of a character rather Transalpine (like that of Dauphiné) than native, are the dialects of the Vaudois population above Pinerolo (v. Morosi, Arch. glott. xi. 309-416), and their colonies of Guardia in Calabria (ib. xi. 381-393) and of Neu-Hengstett and Pinache-Serres in Württemberg (ib. xi. 393-398). The Vaudois literary language, in which is written the Nobla Leyczon, has, however, no direct connexion with any of the spoken dialects; it is a literary language, and is connected with literary Provençal, the language of the troubadours; see W. Foerster, Göttingische gelehrte Anzeigen (1888) Nos. 20-21.]

2. Ladin Dialects (Ascoli, Arch. glott. i., iv. 342 sqq., vii. 406 sqq.; Gartner, Rätoromanische Grammatik (Heilbronn, 1883), and in Grundriss der romanischen Philologie, 2nd ed., i. 608 sqq.; Salvioni, Arch. glott. xvi. 219 sqq.).—The purest of the Ladin dialects occur on the northern versant of the Alps in the Grisons (Switzerland), and they form the western section of the system. To this section also belongs both politically and in the matter of dialect the valley of Münster (Monastero); it sends its waters to the Adige, and might indeed consequently be geographically considered Italian, but it slopes towards the north. In the central section of the Ladin zone there are two other valleys which likewise drain into tributaries of the Adige, but are also turned towards the north,—the valleys of the Gardena and Gadera, in which occurs the purest Ladin now extant in the central section. The valleys of Münster, the Gardena and the Gadera may thus be regarded as inter-Alpine, and the question may be left open whether or not they should be included even geographically in Italy. There remain, however, within what are strictly Italian limits, the valleys of the Noce, the Avisio, the Cordevole, and the Boite, and the upper basin of the Piave (Comelico), in which are preserved Ladin dialects, more or less pure, belonging to the central section of the Ladin zone or belt. To Italy belongs, further, the whole eastern section of the zone composed of the Friulian territories. It is by far the most populous, containing about 500,000 inhabitants. The Friulian region is bounded on the north by the Carnic Alps, south by the Adriatic, and west by the eastern rim of the upper basin of the Piave and the Livenza; while on the east it stretches into the eastern versant of the basin of the Isonzo, and, further the ancient dialect of Trieste was itself Ladin (Arch. glott. x. 447 et seq.). The Ladin element is further found in greater or less degree throughout an altogether Cis-Alpine “amphizone,” which begins at the western slopes of Monte Rosa, and is to be noticed more particularly in the upper valley of the Ticino and the upper valley of the Liro and of the Mera on the Lombardy versant, and in the Val Fiorentina and central Cadore on the Venetian versant. The Ladin element is clearly observable in the most ancient examples of the dialects of the Venetian estuary (Arch. i. 448-473). The main characteristics by which the Ladin type is determined may be summarized as follows: (1) the guttural of the formulae c + a and g + a passes into a palatal; (2) the l of the formulae pl, cl, &c., is preserved; (3) the s of the ancient terminations is preserved; (4) the accented e in position breaks into a diphthong; (5) the accented o in position breaks into a diphthong; (6) the form of the diphthong which comes from short accented o or from the o of position is ue (whence üe, ö); (7) long accented e and short accented i break into a diphthong, the purest form of which is sounded ei; (8) the accented a tends, within certain limits, to change into e, especially if preceded by a palatal sound; (9) the long accented u is represented by ü. These characteristics are all foreign to true and genuine Italian. Ćárn, carne; spelunća, spelunca; clefs, claves; fuormas, formae; infiern, infernu; ördi, hordeu; möd, modu; plain, plenu; pail, pilu; quael, quale; pür, puru—may be taken as examples from the Upper Engadine (western section of the zone). The following are examples from the central and eastern sections on the Italian versant:—

a. Central Section.—Basin of the Noce: examples of the dialect of Fondo: ćavél, capillu; pesćadór, piscatore; pluévia, pluvia (plovia); pluma (dial. of Val de Rumo: plövia, plümo); vécla, vetula; ćántes, cantas. The dialects of this basin are disappearing.—Basin of the Avisio: examples of the dialect of the Val di Fassa: ćarn, carne; ćéžer, cadere (cad-jere); váća, vacca; fórća, furca; gléžia (géžia), ecclesia; oeglje (oeje), oculi; ćans, canes; rámes, rami; teila, tela; néif, nive; coessa, coxa. The dialects of this basin which are farther west than Fassa are gradually being merged in the Veneto-Tridentine dialects.—Basin of the Cordevole: here the district of Livinal-Lungo (Buchenstein) is Austrian politically, and that of Rocca d’ Agordo and Laste is Italian. Examples of the dialect of Livinal-Lungo: ćarié, Ital. caricare; ćanté, cantatus; ógle, oculu; ćans, canes; ćavéis, capilli; viérm, verme; fŭóc, focu; avéĭ, habere; néi, nive.—Basin of the Boite: here the district of Ampezzo (Heiden) is politically Austrian, that of Oltrechiusa Italian. Examples of the dialect of Ampezzo are ćasa, casa; ćandéra, candela; fórćes, furcae, pl.; séntes, sentis. It is a decadent form.—Upper Basin of the Piave: dialect of the Comelico: ćésa, casa; ćen (can), cane; ćaljé, caligariu; bos, boves; noevo, novu; loego, locu.

b. Eastern Section or Friulian Region.—Here there still exists a flourishing “Ladinity,” but at the same time it tends towards Italian, particularly in the want both of the e from á and of the ü (and consequently of the ö). Examples of the Udine variety: ćarr, carro; ćavál, caballu; ćastiél, castellu; fórće, furca; clar, claru; glaç, glacie; plan, planu; colors, colores; lungs, longi, pl.; dévis, debes; vidiél, vitello; fiéste, festa; puéss, possum; cuétt, coctu; uárdi, hordeu.—The most ancient specimens of the Friulian dialect belong to the 14th century (see Arch. iv. 188 sqq.).

B. Dialects which are detached from the true and proper Italian system, but form no integral part of any foreign Neo-Latin system.

1. Here first of all is the extensive system of the dialects usually called Gallo-Italian, although that designation cannot be considered sufficiently distinctive, since it would be equally applicable to the Franco-Provençal (A. 1) and the Ladin (A. 2). The system is subdivided into four great groups—(a) the Ligurian, (b) the Piedmontese, (c) the Lombard and (d) the Emilian—the name furnishing on the whole sufficient indication of the localization and limits.—These groups, considered more particularly in their more pronounced varieties, differ greatly from each other; and, in regard to the Ligurian, it was even denied that it belongs to this system at all (see Arch. ii. III sqq.).—Characteristic of the Piedmontese, the Lombard and the Emilian is the continual elision of the unaccented final vowels except a (e.g. Turinese öj, oculu; Milanese vǫç, voce; Bolognese vîd, Ital. vite), but the Ligurian does not keep them company (e.g. Genoese öģģu, oculu; vǫže, voce). In the Piedmontese and Emilian there is further a tendency to eliminate the protonic vowels—a tendency much more pronounced in the second of these groups than in the first (e.g. Pied, dné, danaro; vśin, vicino; fnôć, finocchio; Bolognese ćprà, disperato). This phenomenon involves in large measure that of the prothesis of a; as, e.g. in Piedmontese and Emilian armor, rumore; Emilian alvär, levare, &c. U for the long accented Latin u and ö for the short accented Latin o (and even within certain limits the short Latin ó of position) are common to the Piedmontese, the Ligurian, the Lombard and the northernmost section of the Emilian: e.g., Turinese, Milanese and Piacentine dür, and Genoese düu, duro; Turinese and Genoese möve, Parmigiane möver, and Milanese möf, muovere; Piedmontese dörm, dorme; Milanese völta, volta. Ei for the long accented Latin e and for the short accented Latin i is common to the Piedmontese and the Ligurian, and even extends over a large part of Emilia: e.g. Turinese and Genoese avéi, habere, Bolognese avéir; Turinese and Genoese beive, bibere, Bolognese neiv, neve. In Emilia and part of Piedmont ei occurs also in the formulae ĕn, ent, emp; e.g. Bolognese and Modenese beiṅ, solaméint. In connexion with these examples, there is also the Bolognese feiṅ, Ital. fine, representing the series in which e is derived from an í followed by n, a phenomenon which occurs, to a greater or less extent throughout the Emilian dialects; in them also is found, parallel with the ḛi from ḛ, the ou from ǫ: Bolognese udóur, Ital. odore; famóus, Ital. famoso; lóuv, lŭpu. The system shows a repugnance throughout to ie for the short accented Latin e (as it occurs in Italian piede, &c.); in other words, this diphthong has died out, but in various fashions; Piedmontese and Lombard deç, dieci; Genoese dēže (in some corners of Liguria, however, occurs dieže); Bolognese diç, old Bolognese, diese. The greater part of the phenomena indicated above have “Gallic” counterparts too evident to require to be specially pointed out. One of the most important traces of Gallic or Celtic reaction is the reduction of the Latin accented a into e (ä, &c.), of which phenomenon, however, no certain indications have as yet been found in the Ligurian group. On the other hand it remains, in the case of very many of the Piedmontese dialects, in the é of the infinitives of the first conjugation: porté, portare, &c.; and numerous vestiges of it are still found in Lombardy (e.g. in Bassa Brianza: andae, andato; guardae, guardato; sae, sale; see Arch. i. 296-298, 536). Emilia also preserves it in very extensive use: Modenese andér, andare; arivéda, arrivata; peç, pace; Faenzan parlé, parlare and parlato; parléda, parlata; ches, caso; &c. The phenomenon, in company with other Gallo-Italian and more specially Emilian characteristics extends to the valley of the Metauro, and even passes to the opposite side of the Apennines, spreading on both banks of the head stream of the Tiber and through the valley of the Chiane: hence the types artrovér, ritrovare, portéto, portato, &c., of the Perugian and Aretine dialects (see infra C. 3, b). In the phenomenon of á passing into e (as indeed, the Gallo-Italic evolution of other Latin vowels) special distinctions would require to be drawn between bases in which a (not standing in position) precedes a non-nasal consonant (e.g. amáto), and those which have a before a nasal: and in the latter case there would be a non-positional subdivision (e.g. fáme, páne) and a positional one (e.g. quánto, amándo, cámpo); see Arch. i. 293 sqq. This leads us to the nasals, a category of sounds comprising other Gallo-Italic characteristics. There occurs more or less widely, throughout all the sections of the system, and in different gradations, that “velar” nasal in the end of a syllable (paṅ, maṅ ; ćáṅta, moṅt)[4] which may be weakened into a simple nasalizing of a vowel (pā, &c.) or even grow completely inaudible (Bergamese pa, pane; padrú, padrone; tep, tempo; met, mente; mut, monte; pût, ponte; púća, punta, i.e. “puncta”), where Celtic and especially Irish analogies and even the frequent use of t for nt, &c., in ancient Umbrian orthography occur to the mind. Then we have the faucal n by which the Ligurian and the Piedmontese (laṉ̇a lüṉ̇a, &c.) are connected with the group which we call Franco-Provençal (A. 1).—We pass on to the “Gallic” resolution of the nexus ct (e.g. facto, fajto, fajtjo. fait, fać ; tecto, tejto, tejtjo, teit, teć) which invariably occurs in the Piedmontese, the Ligurian and the Lombard: Pied, fáit, Lig. fajtu, faetu, Lombard fac; Pied. téit, Lig. téitu, Lom. tec; &c. Here it is to be observed that besides the Celtic analogy the Umbrian also helps us (adveitu = ad-vecto; &c.). The Piedmontese and Ligurian come close to each other, more especially by a curious resolution of the secondary hiatus (Gen. réiže, Piedm. ré̱js = *ra-íce, Ital. radice) by the regular dropping of the d both primary and secondary, a phenomenon common in French (as Piedmontese and Ligurian ríe, ridere; Piedmontese pué, potare; Genoese naeghe = náighe. nátiche, &c.). The Lombard type, or more correctly the type which has become the dominant one in Lombardy (Arch. i. 305-306, 310-311), is more sparing in this respect; and still more so is the Emilian. In the Piedmontese and in the Alpine dialects of Lombardy is also found that other purely Gallic resolution of the guttural between two vowels by which we have the types brája, mánia, over against the Ligurian brága, mánega, braca, manica. Among the phonetic phenomena peculiar to the Ligurian is a continual reduction (as also in Lombardy and part of Piedmont) of l between vowels into r and the subsequent dropping of this r at the end of words in the modern Genoese; just as happens also with the primary r: thus dū = durúr = dolore, &c. Characteristic of the Ligurian, but not without analogies in Upper Italy even (Arch., ii. 157-158, ix. 209, 255), is the resolution of pj, bj, fj into ć, ģ, š: ćü, più, plus; raģģa, rabbia, rabies; šû, fiore. Finally, the sounds š and ž have a very wide range in Ligurian (Arch. ii. 158-159), but are, however, etymologically, of different origin from the sounds š and ž in Lombard. The reduction of s into h occurs in the Bergamo dialects: hira, sera; groh, grosso; cahtél, castello (see also B.2).—A general phenomenon in Gallo-Italic phonetics which also comes to have an inflexional importance is that by which the unaccented final i has an influence on the accented vowel. This enters into a series of phenomena which even extends into southern Italy; but in the Gallo-Italic there are particular resolutions which agree well with the general connexions of this system. [We may briefly recall the following forms in the plural and 2nd person singular: old Piedmontese drayp pl. of drap, Ital. drappo; man, meyn, Ital. mano, -i; long, loyng, Ital. lungo, -ghi; Genoese, káṅ, kḛṅ, Ital. cane, -i; buṅ, buíṅ, Ital. buono, -i; Bolognese, fär, fîr, Ital. ferro, -i; peir, pîr, Ital. pero, -i. zôp, zûp, Ital. zoppo, -i; louv, lûv, Ital. lupo, -i; vedd, vî, Ital. io vedo, tu vedi; vojj, vû, Ital. io voglio, tu vuoi; Milanese quȩst, quist, Ital. questo, -i, and, in the Alps of Lombardy, pal, pȩl, Ital. palo, -i; rȩd, rid, Ital. rete, -i; co̱r, cör, Ital. cuore, -i; ǫrs, ürs, Ital. orso, -i; law, lȩw, Ital. io lavo, tu lavi; mȩt, mit, Ital. io metto, tu metti; mo̱w möw, Ital. io muovo, tu muovi; cǫr, cür, Ital. io corro, tu corri. [Vicentine pomo, pumi, Ital. pomo, -i; pero, piéri = *píri, Ital. pero, -i; v. Arch. i. 540-541; ix. 235 et seq., xiv. 329-330].—Among morphological peculiarities the first place may be given to the Bolognese sipa (seppa), because, thanks to Dante and others, it has acquired great literary celebrity. It really signifies “sia” (sim, sit), and is an analogical form fashioned on aepa, a legitimate continuation of the corresponding forms of the other auxiliary (habeam, habeat), which is still heard in ch’me aepa purtae, ch’lu aepa purtae, ch’io abbia portato, ch’egli abbia portato. Next may be noted the 3rd person singular in -p of the perfect of esse and of the first conjugation in the Forlì dialect (fop, fu; mandép, mandò; &c.). This also must be analogical, and due to a legitimate ep, ebbe (see Arch. ii. 401; and compare fobbe, fu, in the dialect of Camerino, in the province of Macerata, as well as the Spanish analogy of tuve estuve formed after hube). Characteristic of the Lombard dialect is the ending -i in the 1st person sing. pres. indic. (mi a po̱rti, Ital. io porto); and of Piedmontese, the -éjça, as indicating the subjunctive imperfect (portȩjça, Ital. portassi) the origin of which is to be sought in imperfects of the type staésse, faésse reduced normally to sté̱jç-, fé̱jç-. Lastly, in the domain of syntax, may be added the tendency to repeat the pronoun (e.g. ti te cántet of the Milanese, which really is tu tu cántas-tu, equivalent merely to “cantas”), a tendency at work in the Emilian and Lombard, but more particularly pronounced in the Piedmontese. With this the corresponding tendency of the Celtic languages has been more than once and with justice compared; here it may be added that the Milanese nün, apparently a single form for “noi,” is really a compound or reduplication in the manner of the ni-ni, its exact counterpart in the Celtic tongues. [From Lombardy, or more precisely, from the Lombardo-Alpine region extending from the western slopes of Monte Rosa to the St Gotthard, are derived the Gallo-Italian dialects, now largely, though not all to the same extent, Sicilianized, from the Sicilian communes of Sanfratello, Piazza-Armerina, Nicosia, Aidone, Novara and Sperlinga (v. Arch. glott. viii. 304-316, 406-422, xiv. 436-452; Romania, xxviii. 409-420; Memorie dell’ Istituto lombardo, xxi. 255 et seq.). The dialects of Gombitelli and Sillano in the Tuscan Apennines are connected with Emilia (Arch. glott. xii. 309-354). And from Liguria come those of Carloforte in Sardinia, as also those of Monaco, and of Mons, Escragnolles and Biot in the French departments of Var and Alpes Maritimes (Revue de linguistique, xiii. 308)]. The literary records for this group go back as far as the 12th century, if we are right in considering as Piedmontese the Gallo-Italian Sermons published and annotated by Foerster (Romanische Studien, iv. 1-92). But the documents published by A. Gaudenzi (Dial. di Bologna, 168-172) are certainly Piedmontese, or more precisely Canavese, and seem to belong to the 13th century. The Chieri texts date from 1321 (Miscellanea di filol. e linguistica, 345-355), and to the 14th century also belongs the Grisostomo (Arch. glott. vii. 1-120), which represents the old Piedmontese dialect of Pavia (Bollett. della Soc. pav. di Storia Patria, ii. 193 et seq.). The oldest Ligurian texts, if we except the “contrasto” in two languages of Rambaud de Vaqueiras (12th century v. Crescini, Manualetto provenzale, 2nd ed., 287-291), belong to the first decades of the 14th century (Arch. glott. xiv. 22 et seq., ii. 161-312, x. 109-140, viii. 1-97). Emilia has manuscripts going back to the first or second half of the 13th century, the Parlamenti of Guido Fava (see Gaudenzi, op. cit. 127-160) and the Regola dei servi published by G. Ferraro (Leghorn, 1875). An important Emilian text, published only in part, is the Mantuan version of the De proprietatibus rerum of Bartol. Anglico, made by Vivaldo Belcalzer in the early years of the 14th century (v. Cian. Giorn. stor. della letteratura italiana, supplement, No. 5, and cf. Rendiconti Istituto Lombardo, series ii. vol. xxxv. p. 957 et seq.). For Modena also there are numerous documents, starting from 1327. For western Lombardy the most ancient texts (13th century, second half) are the poetical compositions of Bonvesin de la Riva and Pietro da Bescapè, which have reached us only in the 14th-century copies. For eastern Lombardy we have, preserved in Venetian or Tuscan versions, and in MSS. of a later date, the works of Gerardo Patecchio, who lived at Cremona in the first half of the 13th century. Bergamasc literature is plentiful, but not before the 14th century (v. Studi medievali, i. 281-292; Giorn. stor. della lett. ital. xlvi. 351 et seq.).

2. Sardinian language. The third indeed shows Sardinian origin, but the penetration of other elements is surprising, of which South Corsica (Sartene) is by far the most abundant. The other two are homogeneous and have a good relationship; Logudorei received special attention here. Therefore, most Romance languages do not have diphthongs for simple Latin words; this rule does not apply; for example, the representation of ḗ and í on the one hand, and the representation of ṓ and ṹ on the other, respectively, most overlap. Hence plenu (ē deghe, decem (ĕ); Binu (binu), Vino (ī); , nuce (ŭ). Vowels do not like to retain the good root, as seen in rhymes. tenemus; mulghent. — The forms ce, ge, gi may be expressed by che (ke), etc.; the relations cl, &c. may occur at the beginning of a word (claru, plus); although they are close to the parsing of Italian, they are frequently subjected to some parsing, perhaps with very unusual results (e.g. ušare, traceable from the middle letter uscare, from usjare to usclare = ustulare = ustulare). Nź is representative of nj (testimónźu, &c.); the most common changes are ḍḍ: masīḍḍa, palatal, etc. The continuous labialization of forms qua, gua, cu, gu, etc. is very different; e.g. eba, sambene, optimism (see Arch.ii.143). The capital d’s (roere, rodere, etc.) are often deleted, but the small d’s (finidu, sanidade, maduru) are not often deleted. It is also characterized in Logudor by the prosthesis i before the initial s and a consonant following it (iscamnu, istella, ispada), as in Spanish and French e prosthesis (cf. Arch. iii. 447 sq.). – We consider in the following order the changes in the language, the causes of which have for some time been exclusively contact speech, the significance of the events that have occurred, for the first time in the current discussion of this area. from historical legitimacy in the initial consonants. . An example of the final sound preceding it only. A general explanation of this phenomenon is reduced to the fact that, when considering the relationship between two words, the first sign of the second word preserves or changes its character, just as it would like two words to be the same. The Celtic language is particularly famous for this instrument. Among the languages of Upper Italy, Pergamum is a clear example. These words generally drop the v of a vowel in a word, whether primary or secondary (caá, cavare; fáa, fava, etc.), but retain it if preceded by a consonant (serva, etc.). .—Similarly in syntactic pairs, for example, de i, di vino; but ol vi, il vino. In the islands of southern and central Italy, these occurrences are most frequent; su oe, il bove, and sos boes, are represented by i. bui (see One, Pepper; to enter. To wait. (See Arch. ii. 429 square meters). A.1; see C.3b). For example, the following is almost unfairly derived from the old strong perfect tense (like posi, rosi), from which come cantesi, timesi (cantavi, timui), dolfesi, dolui. Evidence of the use and abuse of the strong perfect, however, is provided by the participles and infinitives found in the following group of examples: ténnidu, tenuto parfidu, paso, variability; (Arch. ii. 432-433). Finally, the future tense indicates negation: hapo mandigare (ho a mangiare = manger-ó); in fact contradictory information about future tenses and events also occurs in ancient texts from other parts of Italy. [The Campida manuscript, in the Greek text published by Blanchard and Vecher (Bibliothèque de l’École des Chartes, xxxv. 256-257), dates from the end of the 11th century. Next is the Cagliari MSS. The Vulgar Writings of the Archbishop of Cagliari, Florence, 1905; See Studies in the Novels of Guarnario, vol. 189 etc.), the oldest version of which dates from 1114-1120. The Condaghe di S. Pietro di Silchi (§§ xii.-xiii.), respectively more important for the Logoduro, was published by G. Bonazzi (Sassari-Cagliari, 1900; cf. Meyer-Lübke, Zur Kenntnis des Altlogudoreschen, Vienna, 1902). Veglioto. (Quanero Bay) found its last refuge) and finally ended in 1898. This language, known as Dalmatian, is a language that must be carefully distinguished from the Venetian language, which is still spoken in the cities on the Dalmatian coast. Its features remind us in many ways of Romanian and the Romano-Balkan language represented by the Latin elements of Albanian, but to some extent it also reminds us of Southern languages, especially in the poetic language of vowels. East. An Italian language is also related to Friulian, Istrian and Venetian. Taken together, these characteristics seem to indicate that the Dalmatico is very different from pure Italian breeds such as those from Sardinia. The correct one rejects -s and modifies plural nouns; but it’s not a real standard here, because Italians and Romanians agree on that. A tendency, which we have already noticed and which we will have more reason to notice below, and which links Vigliote and the language of Abruzzo-Apulia in the opposite direction, is found in the reduction of stressed words to diphthongs. Sounds: Examples are some of them: spuota, Italy. Kılıç; Burca, Italy. Barcelona; Fiale, Italy. Iron; Italy, Nuate. Remember; Catania, Italy. Series; Italian Pier. os; lat. Cream; Medium Italian Hit Sau. Walnut; Remember; Otaica, Italy. Otica; Iowa, Italy. To do. Also note other occurrences of the words, such as prut, examples in Italian. Prato; Dick, Italy. Ten, lat. centimeter; with Italy. Member; Italian Accident. Grow; Check this out, Italy. Five grams, lat. Italian bucca; Boca, Lat. BC ordered. Regarding consonants, we must first note the persistence of explosive surds (as in Romanian and southern dialects), of which the few words we have just mentioned will be examples, with the addition of kuosa (Italian). Home; Presa, Italy; Riva. The c in the formula ce, whether primary or secondary, is represented by k: cain, Ital. Senna; Canary, Italy. Senigia; Arquette, Italy. Acetate banner, Italy. lom zam; upright, Italian clan; Givengel; Pruegel, Italy, Piagere, etc. On the contrary, the guttural sound of the original cū formula becomes ć (ćol, Italian. culo); as you are right. Pt save, as in Romanian (sapto, Lat. septem) and often, as in Romanian, ct can be reduced to pt (guapto, Latin octo). In terms of morphology, a feature from Latin has been preserved. Italian avrò cantato is used in the simple future tense. Cantaverum also appears specially. For a comprehensive account of Vegliote and Dalmatico, see M. G. Bartoli’s important works Das Dalmatik (Vol. 2, Vienna, 1906) and Zeitschrift für roman. Linguistics, xxxii. 1 square metre; Merlo, Philology and Classification Class, xxxv. 472 square metres A short document written in the Dalmatian dialect of Ragusa around 1280 can be found in Archeografo Triestino, New Series, Volume 1. I. Pages 85-86.]

C. A language more or less of the true Italian or Tuscan type, but which may also combine with Tuscan to form part of a specific system of neo-Latin dialects.

1. Venetian. 391 m weight. Now, the citizens of the city of Venice are linguistically “Venetian”, but the countryside is in many ways Venetian. The ancient language of Venice and its estuary does not differ much from the language of today. The Latin veins are especially noticeable (see A.2). A purer Italian style, the historical interpretation of which raises an interesting question, eventually became dominant and determined the “Venetian” style, which later spread to the movement. , we do not see the most special thing. In the Gallic parsing of ct there is also no negation of negative words or the negation of the capital of words. Instead, pure Italian vowels ṍ are heard (e.g., cuór), whereas vowel vowels ế are fully rounded (diéśe, dieci, etc.). However, Venetian is close to the northern Italian type or differs from the central Italian type, and the resulting sound is: primary or secondary deletion of d (crúo, crudo; séa, seta, etc.); surd abbreviation for Sonorant guttural sounds (e.g. cuogo, Italian, cuoco, coquus cl, representing pure ć in analysis (e.g. ćave, clave; oréća, auricula ś, śóvene, Italian. giovane); and ć (péçe , Italian. pesce) represents chiel, Italian. Hello). Lj is preceded by a vowel (primary or secondary (except I), giving g: faméga, familia). No Italian is more opposed to the repetition of consonants than the Venetians. iv). 393, shout. est, is particularly notable. An interesting doubling of Bin Laden’s power is the question form, exemplified by crédis-tu, credis tu, which can be used in addition to the question ti credi. For other ancient sites of Venice, the Estuary of Venice, Verona and Padua, see Arches. I. 448, 465, 421-422; 3. 245-247. [Very similar to Venetian, although different from many Gallo-Italian dialects, it is a dialect of Istrian, now almost entirely Venetian and found only in a few places (Rovinho, Dignano). The most distinctive feature of Istrian is visible in the treatment of stressed words and at least in some memories of the Viliot dialect. Thus we have “ệ” in Istrian (bivi, Italian). Beev, Lat. Bibi; Xov, Italy, Vero. vero and vetro, lat. vēru, to see; or Italy. Neeb, Rath. nĭtĭdu etc.), similar in meaning to ǫ (fiur, Italian. fiore, Latin flōre; bus, Italian. voce, Latin). price, etc.); from Latin ei and ou. ī and ū respectively (ameigo, Latin amicu, feil, Latin thread, etc.; mour, Latin mūru; noudu, Latin. Wave; Fruto, Italy. Fruit, lat. fruit, etc.); that is, made from ĕ and ŏ respectively (piel, Lat. pĕlle, mierlo, Italian. merlo, Lat. Merula; Cuorno, Fare. kornu; Puorta, lat. pŏrta), the case in Istria resembles not only Viliot but also Friulian. Note the similarity with Verona, i.e. the unstressed -e suffix is reduced to o (nuoto, Ital. notte, &c., bivo, Ital. Bev; Italian Malamcentro. malamente, etc.) and in the case of Belluno and Treviso correct -óni, -áni (barbói, -oin, Italian. barboni), but especially in Istrian -ain should give -şṅ (kaṅ, kşṅ, Italian. şeker-i). We should note that for consonants n stands for gn (líno, Italian). Lenio); As for morphology, we must take into account the remnants of the inflectional form amita, -ánis (sing. sía, Italian zia, pl. siaṅne). E. Bertanza and V. Lazzarini, Il Dialetto veneziano fino alla morte di Dante Alighieri, Venice, 1891), it appears in the Saibante Manuscript from the second half of the same century. For Verona we also have documents from the 13th century (against Cipolla, Archivio storico italiano, 1881 and 1882); it is preserved for us in the writings of Giacomino da Verona. See also glottal archives, i. 448, 465, 421-422, 3. 245-247: i

2. Corsican [8] – If “Venetian”, despite its special “Italianness”, has a close and special relationship with the other languages of Upper Italy (B.1), then Corsican also really does, especially in the south. variation. which has a special point of contact with the Sardinian people (B.2). Generally speaking, it is the most remote part of Tuscany, in the south of the island, which shows the best features of the language. Unstressed words are of no importance; but u-tuscany, as to Tuscany, is common almost throughout the island; the surprising result is that it is the island that connects Corsica to Sardinia, Sicily, and even Liguria connects them. -i also represents the Tuscan -e (latti, latte; li cateni, le catene), found mainly in the south, also in northern and southern Sardinia and in Sicily. Needless to say, this is more or less clearly expressed in speech for you and me. Corsican also avoids the diphthongs ế and ṍ (pe, eri; cori, fora): unlike Sardinian, however, it treats ḯ and ṍ as Italian: beju, bibo, peveru, bagpiper; 133, 144-150). But the initial inflected gerund in -endu (turnendu, lagrimendu, etc.), on the contrary, must be considered a similar phenomenon, since it is particularly recognized in the Sardinian dialects and is abundant in all of them (see Arch 133). The same would be true for the present participle forms such as tradere, mercante, but enzi and innenzi (anzi, innanzi) are to be traced behind the final form of the power of New Latin I, which was used to reduce the Latin letters. . ; next to them we also find “Anzi” and “Nantu”. But see also grũndi, Italy. Grande. Common from dr to II in southern Corsica, a phenomenon that also connects Corsica with Sardinia, Sicily and much of southern Italy (see C.2; and Arch. 2). ii. 135 et seq.), also includes the northern coast of Tuscany, as examples like beḍḍu are also Carrara and Montinhoso. Also in the Ultramontane variety rn becomes r (= rr) and nd becomes nn (furu, Italian forno; koru, Italian corno; kuannu, Italian). When; Italian Vidennu. Wiedendo). The first connects Corsica with Sardinia (corru, cornu; carre, carne, etc.); a special connection with the central language is achieved by the change of ld to ll (kallu, Italian caldo). 2. Space is left only for the following examples: Cors, na vella, una bella, e bella (ebbélla and bella yellow, cock, rhubarb); 2. 136 (135, 150), xiv. 185. As Tomaseo points out, this termination is less common for the Corsicans than for the Sicilians, Calabrians, and French: for example, frateronu, fratellino. At Rome and elsewhere. Finally, the Corsican verb series of derivational order is juxtaposed with the Italian series of the first order and can be represented by the example dissipate, dissipa (Falcucci), to be compared with the Sicilian verb series represented by cuadiari, riscaldare, curpiári, colpire (Arch. ii. 151).

444 3. Dialect of Sicily and the province of Naples. Sardinian and generally Latin-derived parts are also resistant (see Arch.ii.154, etc.). These words are not always bad; their reduction, especially in Naples the reduction of surd to a consonant, occurs more frequently than in the written word, but their disappearance is rare. Even the derogatory terms are very different from the Upper Italian dialects, both in time and in their specific character. Thus, in Sicilian and Neapolitan the t of the vowels usually remains the same (as in Sicilian.sita, Neap.seta, seta, in Upper Italian dialects it would be seda, deniz); from n or r (as in viendę, vento), it is easy to make d, which is exactly the collocation in Upper Italian where the t remains; while the d is resolved not by dropping it, but by reducing it to r (e.g. Sicil.víriri, Neap. dialects veré, vedere), this phenomenon has often been compared, perhaps less cautiously, with the transformation of d into rs (ḍ) in Umbrian inscriptions. Neapolitan simplifies nt to nd, similarly to nc (nk) to ng, mp to mb (also one of the Neapolitan languages) and ns to nź (nb, mb) (e.g. in Castelmini, ‘mbiernu, inferno’ in Sicilian, ‘cumbonn’, ‘mbonn’, confondere, infondere in Abruzzi). Here we find ourselves in cases where Oscan and Umbrian seem to have made some special contribution (nt, mp, nc to nd, etc.), but for the sake of safety and more it can be said that “isothermal” and. similar expressions also exist in modern Greek and Albanian. In terms of recipes and ingredients, Sicilian does not seem to fit here very well; this can be countered by simplifying nģ and nź to nć, nz (e.g. púnćiri, pungere; menzu, Italian. meźźo; sponza, Italian). Spoona, Ven. Not only that, the Neapolitan language makes a special and important contribution even in the transformation of letters into words (although the Sicilian language is not limited to these, except in the documents just mentioned), in which we say that the d of the vowels is only t. the sound of the final proparoxytones (e.g. úmmeto, Sicil. úmitu, umido) and in the formula dr (Sicil. and Neap. quatro, Ital. Sib, etc.). From this series of consonants turning into surd, a special feature of the southern dialects arises. mm and even nv are simplified to mm (nv, nb, mb, mm), as in Sicil. Snini, Neeb. sennere, yer; Chim, Neeb. Chiummę, piombo; Sicily. and Nip. ‘Media, Invidia; Sicily. Sanger, Sib. As an old Italian analogue of the phenomena belonging to this class (nd to nn, n), the Umbrians afford special evidence which readily suggests itself. Another important point is that the minor pj fj is reduced to kj and the minor bj to j (chianu -ę, Sicil., Neap., &c., Ital. piano), š (Sicil. šúmi, Neap. šúmmę, fiume) (can be strengthened to ghj) is the beginning (Sicil.jancu, Neap. Jance, white; agghianchiari, whitening) are among the vowels (Neap. neglia, nebbia, Sicil. nigliu, nibbio); séćca, seppia) or gr (Sicil. raģga, Neap. arraģģa, rabbia), these cases are also found in Genoese (B.1). More important is CJ’s feelings towards Sicil. Jazzu, ghiaccio may be given as an example (Arch. ii. 149), a peculiar favourite in Upper Italy, but not in the Abruzans (cf. Abr. jacce, ghiaccio, vracce, braccio, etc.). There is also a tendency to eliminate the palatal consonant and to precede it with a, especially before r (a second tendency is also observed in Southern Sardinia, etc.; cf. Arch. 138, Sicil. ‘ndénnere; Arricari, Neeb. arragamare, ricamare (see Arch.ii.150). Throughout the region and also in neighbouring parts of central Italy there is a tendency to decipher certain communications by combining the letters r or l, w or j (Sicilian). kiruci, Italian, filagutu, flute, spit, tseg, variva, Italian; Calecene, Ltalis. ganghero, Salvester, Sylvester, fly, tag, jackal, Italian. Hidden herb; ávotro = *awtro, Italian. diğer, wine = *wine, Italy. milk, good or bad good, Ltalis. Age, ódejo = ódjo, hatred, etc.; ‘nnívęję, indiva, nệbbęję, thorn, etc.); and c., exemplified by Molfetta, where the resolution of šk from šek (méšekere, mask, šekátele, box, etc.) is also common in some languages of Avellino, from “seddegno”, meaning “contempt”. In contrast to the specific preference for moving away from doubling words noted in Venetian (C.1), here we come to the Great Schism of Italy, where the tendency to double words (or to double words) was stronger, especially in acetaminophen. ; Neapolitan goes further than Sicilian in this respect (e.g. Sicilian. sóggiru, suocero, cínniri, cenere, doppu, dopo; ‘nsemmula, insieme, in-simul; Neap. dellecato, dilicato; úmmeto, umbido; ćincu jorna, cinque giorni, with chiú ghiorna, più giorni and la vocca, with la bocca in Neapolitan, as well as bocca, ad buccam, etc.

We will now consider, first of all, the Sicilian language, and secondly, the national language, in particular.

(a) Sicily. Although different in colour from Tuscan, it is no less noble, and there are important points of contact between the two. Most of the important things represented in written words omit the vowels ḗ and ŏ, as we have seen omitted in Sardinian (B.2), where ĭ and ŭ also appear negative; and y; just as symmetrically, the unstressed e and o are reproduced by i and u. Examples: téni, tener, nóvu, new; crídiri, to believe; vínniri, Italy; Fame. In the evolution of consonants it is sufficient to add here the change of lj to ghj (like figghhiu, Italian, figlio) and ll to ḍḍ (like gaḍḍu, Italian, gallo). As for morphology, we will limit ourselves to showing the most masculine form of the neutral (like pastura, like marinara). For Sicilian we have some fragments dating back to the 13th century, but information is scarce up to the 14th century.

(b) Neapolitan continental language. – heart heart; Femina, female voice, Ure, Honore; reduced to both Sicilian and Calabrian rr (Sic. parrari, Cal. parrare, parlare, etc.). The final vowel -e is reduced to -i, but retained further south, as in the example above. Even ḣ means š = fj; as in ḣuri (Sicilian šuri, fiore), which is native to Calabria and has its antecedents on the island (cf. Arch ii. 456). And likewise, although there are many important names such as mb instead of lo in Calabria (sometimes taking the form mm mb: imbiscare = Sicil. ‘mmiscari ‘immischiare’ etc.) and nd instead of um, nn, in the south. Italy and Sicily, we must remember first of all that there are some animals there, such as Grandmother, Italian. Grande and Chimu, Italian. Piombo; secondly, the use of nd can be seen even in Sicily (as far as Milazzo, Barcelona and Messina). When we passed the explosion caused by the Basilisco type (known as Basilicata) on the southern coast of Italy, Sicilian music reappeared in Otrantini, especially on the coastal card of Capodileu. In the Lecce variety of Otrantin, the sounds identified exclusively as Sicilian still retain their original places (cf. Morosi, Arch. iv.): sira, sera, oliveto; not only that, but also the Sicilian lj for ghj (figghiu, figlio, etc.) appears in Terra d’Otranto and Terra di Bari, and even extends as far as Capitanata and Basilicata (cf. D’Ovidio, Arch). 4. 159-160). The characteristic of the Otranto region is the island that appears from ll to ḍḍ (ḍr), which also extends in the region of Naples east of the Apennines and even extends its branches to the Abruzzo River. But in the “Terra d’Otranto” we are already in the middle of the diphthong ế and ṍ, both non-positional and positional; its development or permanence depends on the quality of the final unstressed vowel, as in Most. South. The vowels ế and ṍ are determined by the final -i and -u and are characteristic of central and northern Calabria (viecchiu -i, vecchio -a, vecchia -e, vecchia -e; buonu -i , bona -e toss). &C. Thus the treatment of the vowels specific to the two peninsulas of Calabria and Salente emerges. The diphthong of O is here. The following are examples of variants of the Lecce dialect: core, pl. metu, mieti, mete, mieto, mieti, miete (Latin: M); Centu, Centi, Cente; ue recalls the diminutive of the Gallic lands (not to mention Spain) and extends north of Terra di Bari, where other vowels are strangely represented in Gaul: for example, next to Bitonto, we have luechę, luogo, suęnnę, sonno, oi and ai (vęćoinę, vicino) at the level of the previous i or ę, and au (anaurę, onore) at the level of the previous o, plus the uncertain diphthong of á. Here too the transition from á to a more or less pure e occurs (so in Cisternino suncsulête, sconsolata; in Canosa di Puglia arruête, arrivata; n-ghèpe, “in capa”, for example in capo plus other). Unstressed vowels are always weak or removed not only at the end but also in the body of the word (hence in Bitonto, vendett, spanz). When we enter the Capitanata we encounter similar types (Cerignola: graitę and grēi-, creta (also pęitę, piede, etc.), coutę, coda (also fourę, fuorí, etc.); vǫinę, vino, etc.) pǫilę, pelo (Neap. pilo), etc.; fuękę, fuoco; carętätę, carità, parlä, parlare, etc.); the population is large and not numerous, and in the past the population was more diverse – the history continues with some influence from the popular language, the common name of the Adriatic dialects, thus influenced by the other side of the Apennines. speak In Agnone, in the valley at the head of the Molise River, the legal antecedents of the Abruzzo language reappear (feáfa, fava, stufeáte and -uote, stufo, annojato, feá, fare; chiezza, piazza, pianre, cane; puole, pruote, baston; the following are also Abruzza examples (1) from Bucchiianico, in raję, king, then, road, path (again, it can be seen that the reduction of á depends on the quality of the ending), and was not created by me; (2) from Pratola Pellegna (Ultriio II of Abruzzo); beyond the border region (elsewhere a greater influence of “Italianism” has appeared; the third part of the dubious history of Venice); has already been mentioned. 1); see arc. ii., 445. The disadvantage of Abruzzi is that there is no change in the three sounds of the combination pl, bl, fl (which becomes kj, j-, š), the reason for which is obvious. Here pj, bj and fj seem to be modern or new simple – old forms sometimes occur in their entirety (as in the Italian Pergamene above), for example plánje and pránje and piánje, piagnere, branghe and bianghe, bianco (Fr. . blanc), groove and frame and smoke, smoke. Starting from the south of the Abruzzi, where this difference becomes important in the lower ald formula (in Neapolitan and Sicilian, as in Piedmontese, it is resolved as aut etc.),

As for the original centre of the Italian language, it must be considered that it is not limited to the narrow confines of Tuscany, as described above; it can clearly be associated only with the city of Florence. It can therefore be said that, with the exception of a few words taken from other Italian languages, all words other than Tuscan have been eliminated from the text of the language, since some words were taken from foreign languages. If we go back to Dante’s time, we find that in almost all continental dialects other than Tuscan, the alternation of the singular and plural vowels in “paese”, “paisi” quello, quilli amore, amuri (cf. B. 1; C. 3b); but the written language knows nothing of this event, since it was unknown in Tuscany. But in Tuscany there is a difference between Florentines and non-Florentines. For example, in Florence it is said and often said “to”, “giunto”, “punto”, whereas non-Florentines say “to”, “gionto”, “ponto” (Latin unctu, etc.); in Florence they say “piazza”, “meźźo”, elsewhere (Lucca, Pisa) they say or pronounce “piassa”, “meśśo”. It is now the Florentine form that stands alone in written language.

In old works containing bad language, especially in poetry, non-Tuscan writers modified their dialects, on the one hand, to what they considered the purest representatives of the language of ancient Roman culture, while on the other hand, Tuscan writings were rejected by the writers of Cana. Illuminationists from other parts of Italy wrote to accept the form of citizenship. It is this situation that has given rise to many debates in the past about the true homeland of Italy and the origin of his writings. But when the history of words is examined, these words have been deprived of their right to exist. Although ancient Italian poetry had taken or preserved different forms of the Tuscan language, these forms were gradually eliminated and the world was left entirely to Tuscan and even Florentine poetry. Thus in no European language is there a greater unity and solidity of sounds, morphology, basic concepts, in short, of all the qualities and material of words and sentences.

But on the other hand, it is equally true that, as far as the use of the written word and the reliability and integrity of the structure are concerned, the Tuscan or Florentine fabrics support all the civilization and culture of the Italians. still exist. The situation of the Italian nation seems more fortunate than that of other European countries, despite the great changes. Modern Italy does not have a beautiful national living space where thoughts and words can flow without stopping and be assimilated by everyone. Florence is not Paris. The connections between the regions and the small differences in the local languages contributed to the advancement of the spoken language of modern Rome to the written language of Tuscany. What emerged is a fine example of how the language of a city can change when it becomes the language of a country that grows in prosperity, although it lacks the beauty and wealth of Florence. In this case, the dialect has lost its freshness as well as its slang and narrow locality. But it has learned to share the thoughts and feelings of different people, mixed together in a country life, with a willingness and more dignity. But what happened easily in Rome could not happen as easily in a region whose language was far from Tuscany. In Piedmont or Lombardy, for example, the spoken language does not correspond to the language of books, and so the language of books is a stupid and difficult task. Poetry suffers the least from these negativities. Because poetry works so well with different languages that the need for and support for the character of the author are more apparent. But language has suffered greatly, and Italians have every reason to envy the identity and confidence of foreign literature, especially French literature. This legitimate envy is the cause and strength of the Manzoni school, which aims at the dignity of the written word, the accuracy of the spoken language, and the language of the book paper, which most Italians can only manage and control. Manzoni’s rebellion against the influence and popularity of language and style is essential to his skill, and achieves great results. But the different histories of France (using the colloquial language of Paris) and Italy (using the colloquial language of Florence) mean that more than one principle is difficult to grasp; it is the spontaneous product of civilization as a whole. Manzoni’s feelings give rise to an inexpressible sadness. People are falling for a new fashion, a style of writing that might be called bad language or slang. The solution to this problem must lie in directing the work of today’s Italian intellectuals to a more widespread, always passionate, and more integrated approach.

The earliest Tuscan record is a short version of a troubadour’s song (12th century; see Monaci, Crestomazia, 9-10). Nothing survives of this until the 13th century. P. Santini published in 1211 a considerable part of the books written about some Florentine businessmen. It is of interest by the monuments. It dates from 1278 AD. Among them is preserved the Pistoian version of the Tratati Ethics attributed to Sofredi del Gracia by Albertano. Ricardo’s Tristano, printed and annotated by E. G. Parodi, appears to date from the 13th and early 14th centuries. For other 13th-century manuscripts, see Monaci, op. cit. 31-32, 40 and Parodi, Journal of the History of Italian Literature, x. 178-179: I. For more on the language, see Ascoli, Arch. This. v. Vb.; Naples, 1895. L. Fenot gave a beautiful summary of the Italian language in the third volume of his Roman Studies (Zurich, 1806-1808). The dawn of a powerful science had not yet dawned; but Fëanor’s vision was broad and friendly. The same praise is attributed to Biondelli’s Sui dialetti gallo-italici (Milan, 1853), but this book was unknown to Dietz. Between Fernow and Bindelli, August Fuchs was now familiar with the new system. But his research (Über die sogennenten irregelmässigen Zeitwörter in den romanischen Sprachen, nebst Andeutungen über die wichtigsten romanischen Mundarten, Berlin, 1840) was useful but unsuccessful. Can’t Friedrich Dietz’s rapid learning of the Italian language is one of the most impressive of his great talents. The first among Dietz’s followers outside Italy were Musafia, master of the mysterious face and mystery, and Hugo Schuchardt, a private scholar. Later came the Archivio glottologico italiano (Turin, 1873 and later. 16 volumes published from 1897), pioneered by Ascoli and G. Flechia (d. 1892); This book, along with The Dalmatians, was written by Adolf Mussafia (d. 1906) can be considered the founder of the Italian scientific language, which used a strict method based on history and comparison in its studies and achieved the best results. In the study of history in relation to special discourses, Nannucci stands out for his common sense and broad vision. Here we need only mention his Analisiritica dei verbi italiani (Florence, 1844). But the new way is to teach what he does, what he does. When the sport of the above scientists became known, other enthusiasts quickly joined them and soon the arches followed. It was founded in the school of glottology and began to produce many famous linguistics [The first, arranged according to history and virtue, U. A. Canelo (1887), Arch. glottis. 3.285-419; and History of the Italian Poetic Language, N. Caix (d. 1882), (Florence, 1880)] and linguistic studies. Here we will list the most prominent ones for one reason or another. But as far as the study of many cases is concerned, we must first note that there is another view on the distribution of the Italian language (see the various notes on B.1, 2 and C. above). 2) los ntawm W. Meyer-Lübke (Introduction to Studies in Romance Philology, Heidelberg, 1901; pp. 21-22) and M. Bartoli (Ancient Italian Chrestomathy, P. Savj-Lopez and M. Bartoli). Bartoli, Strasbourg, 1903, pp. 171ff. 193, etc. and the table at the end of the volume). W. Meyer-Lübke later added the details of the system he had prepared to the second edition of Gröber’s Grundriss der romanischen Philologie. (1904), p. 696 and following. This masterpiece is the “Italinische Grammatik” (Leipzig, 1890) by the same author, in which words and phrases are placed in an organic whole, just as they are put together in language. A short introduction to the Italian language. Section – Grundriss is mentioned (page 637 etc.). We will now give a list, but from his work, which is discussed throughout the text, we will deduce the following: B. 1 a: Parodi, ib. Grote. 14,1 m², xv. 1 sqft,16. 105 m² 333 m²; Century tabby cat. Seventeen. Photo: E. G. Parodi (Spezia, 1904); Schödel, Ormea Lehçesi (Halle, 1903); Saib; b: Giacomino, Archie. pek tsib. 403 m2; Ib. Ascoli (Turin, 1901), 247 m²; Renier, Il Gelindo (Turin, 1896); Volume II XXXVII. 522 square meters; Romanticism, ii. 1 square meter. Great. 9.188 m weight. Thirteen. 3 55 sq. Lendich. East side. Lum. S. Package 2 Thirty-five. 905 m x ; 4 77 m; Section 569 603 square meters, XLIV. Tshooj 719 Italian Swiss History Bulletin, page xya. thiab the yim. Michael, Poschiavo Vadisinin Lub Lehçesi (Halle, 1905); v. Ettmayer, Bergamask Alp Lehçesi (Leipzig, 1903); 321 sq ft.; d: Mussafia, tus sawv cev ntawm Romagna lus (Viyana, 1871); Bologna şehrinin (Turin, 1889); Search. Bologna. Introduction to the phoneme and definition of dialect by A. Trauzzi (Bologna, 1901, Bertoni, The Dialect of Modena (Turin, 1905); date 673) (Rocca S. Casciano, 1895); Piagnoli, Parma phonetics (Turin, 1904); 372 m²; xiv 133 m²; 197 million quarter weight B.2: Hofmann, Dialect of Logudore and Campidanis (Malburg, 1885); Wagner, Phonology of the Southern Sardinian Dialects (Malle a. S., 1907); Guarnario, Arch. Kaum peb. 125 square meters, hardly convincing. 131 m2, 385 m2 C.1: Rossi, Letters of Mr. Andrea Carmo (Turin, 1888, Paduan dialect near Ruzante (Breslau, 1889); xyoo pua. not very vulgar. There are drawings and notes about V. Cian, with Notes and Definitions of Words edited by C. Salvioni (Vol. 2, Bologna, 1893-1894); Suitable for Romans. Fillol XVI, 183 m², 306 m²; glottis kaum altı. 245 m2 ft.; Vidossich, Studies on the Trieste dialect (Trieste, 1901); Tshooj 749 Ascoli, Archie. du. 14.325 m² işletim sistemi Schneller, Lub Romantic Vernacular ntawm South Tyrol, i. (Guerra, 1870); los ntawm Slop, Tridentine Dialect (Klagenfurt, 1888); C 2: Guarnario, Archie. Grote. 13. 125 feet kare, kaum plaub. 131 m², 385 sq. C.3a: Vintrup-Pitre, Pitre, Fiabe, Sicilian Fiction and Popular Stories, Vol. i., page xxviii. sq.; The Snow Goose, The Sicilian Voice and Voice Development. Dialects (Strasbourg, 1888); 16. 479 m2; La Rosa, Treatise on Sicilian Morphology, n. Noun (Noto, 1901); East side. Lum. S. category 2xl. 1046 ft kare, 1106 ft kare, 1145 ft kare b: Scerbo, On the Calabrian dialect (Floransa, 1886); Calabrese (Castrovillari, 1895); Gentili, Phonetics of the Cosenza dialect (Milan, 1897, Kev Pabcuam rau Kev Paub Txog Napoli Lehçesi (Wittenberg, 1855); Subak, “Napoliten Çekimi, 1897); Achie. 4. 117 ft kare; Tarent (Trani, 1897), The Time in the Art of Tarent (Brun, 1897); See: Maglie d’Otranto (Milan, 1903); Bari, Ntu 1, “Lub Suab Nkauj Niaj Hnub” (Milan, 1896); Barese (Avelino, 1896); 15. 83 m², 226 m²; 171 ft²; Deovidius, Mimar. glottis plaub. 145 ft kare, 403 ft kare; , 1901); Delores, Arch. 12. 1 ft kare, 187 ft kare; Ascoli, 275 m²; Savini, Definition and Interpretation of the Dials. Teramo (Turin, 1881). Vol. 4: Merlo, Zeitschr. F. Roman Phil, xxx. 11 sq. ft., 438 sq. ft., xxxi. 157 sq. ft.; E. Monks (Notes on Ancient Rome), Rendic. of the Lincei, 21 Şubat 1892, s. 94 m²; Rosie Cassel, Bolet. depolama. Abruzzi Evi, vi. Crocione, Zaser. Monk, p. 429 square meters; Ceci, Archie. glottisX. 167 square feet; parody, medicine that answers to no. 13.299 m2; Campanelli, Phonetics of Translation. Ritino (Turin, 1896) Verga sings with Sonnets and other poems by R. Torelli. Perugia (Milan, 1895); Bianchi, Dialect and Ethnography of Castello (City of Castello, 1888); Phil. 273 ft2, 450 ft2; Roma, IX. 617 sqm; Kev Kawm Txuj Ci, FASC. No. 3, 113 ft2, Dial. Alchevia (Rome, 1906); Building 5, 237 m²; Crocione, ib D.: Parodi, Romanya, Glottis XII 107 ft², 141 ft², 161 ft²; Caix-Canero, 305 ft²; Rau Roman Ferrol. 28. 161 ft²; Salvioni, Arch. 16. 395 ft²; Hirsch, Roman Philol’s Dergisi. Cuaj. 513x, cry. 56 sq. ft., 411 sq. ft. Used by the North American peoples in the XV The meaning of all Italian languages (but mostly the languages of northern Italy) has been studied. Jahrhundert from advertising. Etymology of Mussafia (Vienna, 1873) and Giov’s Postille. Fleji (Arsch. The great. ii., iii.) are the most important. Biondelli’s book is also important in the many translations of The Prodigal Son, including the Lombardy, Piedmontese, and Emilian dialects. Zuccagni Orlandini’s Raccolta di dialetetti italiani con illustrations etnologiche (Florence, 1864) contains translations into various Italian languages. Each section is fully represented in the text of Boccaccio’s short story, which Papanti published in Certaldo under the title I Parlari italiani. (Levorno, 1875).

[A very important and rich collection of commentaries on the oldest documents from all over Italy can be found in E. Monaci’s Crestomazia italiana dei primi secoli (Città di Castello, 1889-1897); see also P. Savj-Lopez and Altitalienische Chrestomathie, by M. Bartoli (Strasbourg, 1903). I.A.; CS.

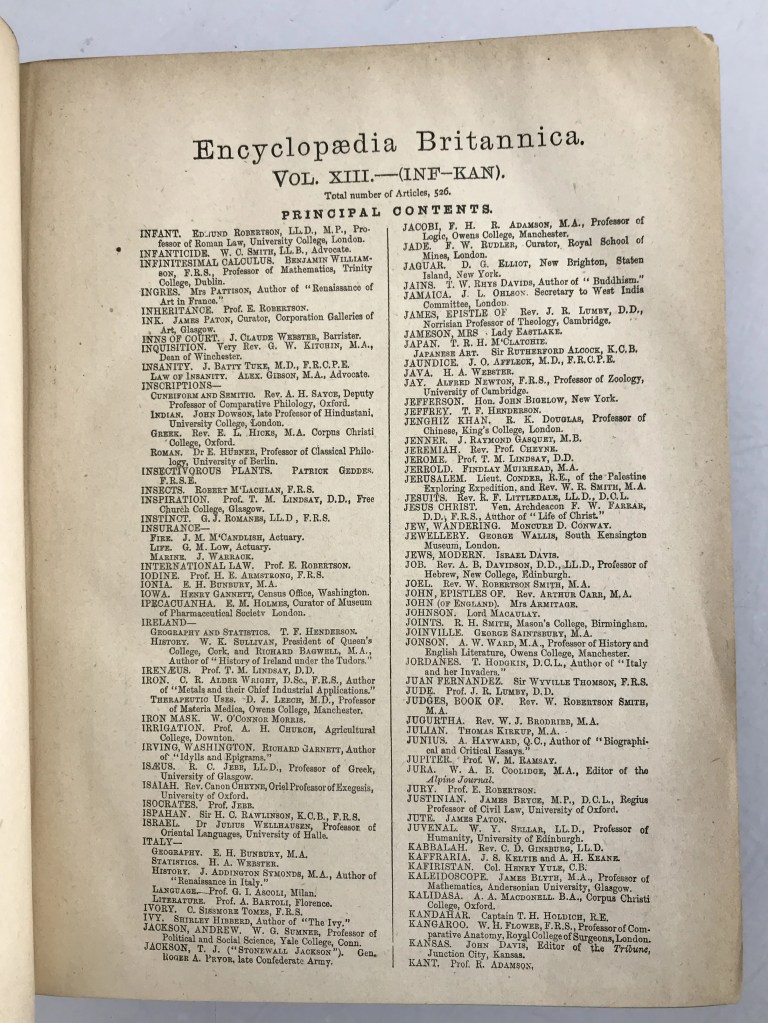

- ↑ The article by G. I. Ascoli in the 9th edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica, which has been recognized as a classic account of the Italian language, was reproduced by him, with slight modifications, in Arch. glott. viii. 98-128. The author proposed to revise his article for the present edition of the Encyclopaedia, but his death on the 21st of January 1907 prevented his carrying out this work, and the task was undertaken by Professor C. Salvioni. In the circumstances it was considered best to confine the revision to bringing Ascoli’s article up to date, while preserving its form and main ideas, together with the addition of bibliographical notes, and occasional corrections and substitutions, in order that the results of more recent research might be embodied. The new matter is principally in the form of notes or insertions within square brackets.

- ↑ [In Corsica the present position of Italian as a language of culture is as follows. Italian is only used for preaching in the country churches. In all the other relations of public and civil life (schools, law courts, meetings, newspapers, correspondence, &c.), its place is taken by French. As the elementary schools no longer teach Italian but French, an educated Corsican nowadays knows only his own dialect for everyday use, and French for public occasions.]

- ↑ [It may be asked whether we ought not to include under this section the Vegliote dialect (Veglioto), since under this form the Dalmatian dialect (Dalmatico) is spoken in Italy. But it should be remembered that in the present generation the Dalmatian dialect has only been heard as a living language at Veglia.]

- ↑ As a matter of fact the “velar” at the end of a word, when preceded by an accented vowel, is found also in Venetia and Istria. This fact, together with others (v. Kritischer Jahresbericht über die Fortschritte der roman. Philol. vii. part i. 130), suggests that we ought to assume an earlier group in which Venetian and Gallo-Italian formed part of one and the same group. In this connexion too should be noted the atonic pronoun ghe (Ital. ci-a lui, a lei, a loro), which is found in Venetian, Lombard, North-Emilian and Ligurian.

- ↑ [The latest authorities for the Sardinian dialects are W. Meyer-Lübke and M. Bartoli, in the passages quoted by Guarnerio in his “Il sardo e il côrso in una nuova classificazione delle lingue romanze” (Arch. glott. xvi. 491-516). These scholars entirely dissociate Sardinian from the Italian system, considering it as forming in itself a Romance language, independent of the others; a view in which they are correct. The chief discriminating criterion is supplied by the treatment of the Latin –s, which is preserved in Sardinian, the Latin accusative form prevailing in the declension of the plural, as opposed to the nominative, which prevails in the Italian system. In this respect the Gallo-Italian dialects adhere to the latter system, rejecting the –s and retaining the nominative form. On the other hand, these facts form an important link between Sardinian and the Western Romance dialects, such as the Iberian, Gallic and Ladin; it is not, however, to be identified with any of them, but is distinguished from them by many strongly-marked characteristics peculiar to itself, chief among which is the treatment of the Latin accented vowels, for which see Ascoli in the text. As to the internal classification of the Sardinian dialects, Guarnerio assumes four types, the Campidanese, Logudorese, Gallurese and Sassarese. The separate individuality of the last of these is indicated chiefly by the treatment of the accented vowels (dḛźi, Ital. dieci; tḛla, Ital. tela; pȩlu, Ital. pelo; nǫbu, Ital. nuovo; fio̱ri, Ital. fiore; no̱źi, Ital. noce, as compared, e.g. with Gallurese dḛci, tḛla, pilu, nou, fiǫri, nući). Both Gallura and Sassari, however, reject the –s, and adopt the nominative form in the plural, thus proving that they are not entirely distinct from the Italian system.]

- ↑ On this point see the chapter, “La terra ferma veneta considerata in ispecie ne’ suoi rapporti con la sezione centrale della zona ladina,” in Arch. i. 406-447.

- ↑ [There are also examples of Istrian variants, such as laṅna, Ital. lana; kadeṅna, Ital. catena.]

- ↑ [There have been of late years many different opinions concerning the classification of Corsican. Meyer-Lübke dissociates it from Italian, and connects it with Sardinian, making of the languages of the two islands a unit independent of the Romance system. But even he (in Gröber’s Grundriss, 2nd ed., vol. i. p. 698) recognized that there were a number of characteristics, among them the participle in –utu and the article illu, closely connecting Sassari and Corsica with the mainland. The matter has since then been put in its true light by Guarnerio (Arch. glott. xvi. 510 et seq.), who points out that there are two varieties of language in Corsica, the Ultramontane or southern, and the Cismontane, by far the most widely spread, in the rest of the island. The former is, it is true, connected with Sardinian, but with that variety, precisely, which, as we have already seen, ought to be separated from the general Sardinian type. Here we might legitimately assume a North-Sardinian and South-Corsican type, having practically the same relation to Italian as have the Gallo-Italian dialects. As to the Cismontane, it has the Tuscan accented vowel-system, does not alter ll or rn, turns lj into ĩ (Ital. gli), and shares with Tuscan the peculiar pronunciation of ć between vowels, while, together with many of the Tuscan and central dialects, it reduces rr to a single consonant. For these reasons, Guarnerio is right in placing the Cismontane, as Ascoli does for all the Corsican dialects, on the same plane as Umbrian, &c.]

- ↑ The Ultramontane variety has, however, tela, pilu, iḍḍu, boći, gula, furu, corresponding exactly to the Gallurese tela, pilu, Ital. pelo, iḍḍu; Ital. “ello,” Lat. illu; bǫci, Ital. voce; gula, Ital. gole.

- ↑ [Traces are not lacking on the mainland of nģ becoming nć, not only in Calabria, where at Cosenza are found, e.g. chiáncere, Ital. piangere, manciare, but also in Sannio and Apulia: chiance, monce, Ital. mungere, in the province of Avellino, púnci, Ital. (tu) pungi, at Brindisi. In Sicily, on the other hand, can be traced examples of nć nk nt mp becoming nģ ng nd mb.]

- ↑ It should, however, be noticed that there seem to be examples of the é from á in the southern dialects on the Tyrrhenian side; texts of Serrara d’Ischia give: mancete, mangiata, maretete, maritata, manneto, mandato; also tenno = Neap. tanno, allora. As to the diphthongs, we should not omit to mention that some of them are obviously of comparatively recent formation. Thus, examples from Cerignola, such as lęvǫitę, oliveto, come from *olivítu (cf. Lecc. leítu, &c.), that is to say, they are posterior to the phenomenon of vowel change by which the formula ę-u became í-u. And, still in the same dialect, in an example like gré̱jtę, creta, the ej seems perhaps to be recent, for the reason that another é, derived from an original é (Lat. ĕ), is treated in the same way (péjte, piede, &c.). As to examples from Agṇone like puole, palo, there still exists a plural pjéle which points to the phase *palo.

- ↑ We should here mention that callu is also found in the Vocabolario Siciliano, and further occurs in Capitanata.

- ↑ This is derived in reality from the Latin termination -unt, which is reduced phonetically to -u, a phenomenon not confined to the Abruzzi; cf. facciu, Ital. fanno, Lat. faciunt, at Norcia; crisciu, Ital. crescono, Lat. crescunt, &c., at Rieti. And examples are also to be found in ancient Tuscan.

- ↑ [This resolution of –ć– by š, or by a sound very near to š, is, however, a Roman phenomenon, found in some parts of Apulia (Molfettese lausce, luce, &c.), and also heard in parts of Sicily.]

- ↑ There is therefore nothing surprising in the fact that, for example, the chronicle of Monaldeschi of Orvieto (14th century) should indicate a form of speech of which Muratori remarks: “Romanis tunc familiaris, nimirum quae in nonnullis accedabat ad Neapolitanam seu vocibus seu pronuntiatione.” The alt into ait, &c. (aitro, moito), which occur in the well-known Vita di Cola di Rienzo, examples of which can also be found in some corners of the Marches, and of which there are also a few traces in Latium, also shows Abruzzan affinity. The phenomenon occurs also, however, in Emilian and Tuscan.

- ↑ A distinction between the masculine and the neuter article can also be noticed at Naples and elsewhere in the southern region, where it sometimes occurs that the initial consonant of the substantive is differently determined according as the substantive itself is conceived as masculine or neuter; thus at Naples, neut. lo bero, masc. lo vero, “il vero,” &c.; at Cerignola (Capitanata), u mme̱gghie̱, “il meglio,” side by side with u mo̬ise̥ “il mese.” The difference is evidently to be explained by the fact that the neuter article originally ended in a consonant (-d or –c?; see Merlo, Zeitschrift für roman. Philol. xxx. 449), which was then assimilated to the initial letter of the substantive, while the masculine article ended in a vowel.

- ↑ This second prefix is common to the opposite valley of the Metauro, and appears farther south in the form of me,—Camerino: me lu pettu, nel petto, me lu Seppurgru, al Sepolcro.

- ↑ A complete analogy is afforded by the history of the Aryan or Sanskrit language in India, which in space and time shows always more and more strongly the reaction of the oral tendencies of the aboriginal races on whom it has been imposed. Thus the Pali presents the ancient Aryan organism in a condition analogous to that of the oldest French, and the Prakrit of the Dramas, on the other hand, in a condition like that of modern French.

Leave a comment