Dougga was a Berber, Punic, and Roman settlement near present-day Téboursouk in northern Tunisia. The present archaeological site encompasses a total area of 65 hectares (160 acres). According to UNESCO’s 1997 designation as a World Heritage Site, Dougga is regarded as the most well-preserved Roman small town in North Africa. The site, which lies in the middle of the countryside, has been protected from modern urbanization, in contrast, for example, to Carthage, which has been pillaged and rebuilt on numerous occasions. The size of Dougga, its well-preserved monuments, and its extensive Numidian-Berber, Punic, ancient Roman, and Byzantine history render it exceptional. Among the prominent monuments situated at the site are the Libyco-Punic Mausoleum, the Capitol, the Roman theatre, and the temples of Saturn and Juno Caelestis.

Names are given by names.

The Numidian name of the settlement was recorded in the Libyco-Berber alphabet as TBGG. The Punic name of the settlement was recorded as TBGG () and TBGG ( Camps states that this may represent a borrowing of a Berber word derived from the root tbg (to protect) The name was derived from Latin as Thugga. When it was granted free status, it was formally refounded and known as Municipium Septimium Aurelium Liberum Thugga. “Septimium” and “Aurelium” refer to the town’s founders, Septimius Severus and M. Aurelius Antoninus. For further treatment of liberum, see below. After Dougga was granted the status of a Roman colony, it was officially referred to as Colonia Licinia Septimia Aurelia Alexandriana Thuggensis.

In contemporary Berber culture, it is commonly referred to as either Dugga or Tugga. Doggi (Arabic: or ) was borrowed into Arabic as Doggi, and Dougga is a French transcription of this Arabic name.

The location is

Dougga’s location in Roman Africa is located in Dougga’s hometown.

The archaeological site is located 4.6 km (2.9 mi) SSW of the modern town of Téboursouk on a plateau with an uninhibited view of the surrounding plains in the Oued Khalled. It offers a high degree of natural protection. The slope on which Dougga is built rises to the north and is bordered in the east by the cliff known as Kef Dougga. Further to the east is the ridge of the Fossa Regia, a ditch and boundary made by the Romans.

Historiography.

The history of Dougga is best known from the time of the Roman conquest, even though numerous pre-Roman monuments, including a necropolis, a mausoleum, and several temples, have been discovered during archaeological digs. These monuments serve as a sign of the significance of the site prior to the arrival of the Romans.

Berber Kingdom is a Berber kingdom.

The remains of the walls were once believed to be Numidian fortifications.

Several historians believe that Dougga was founded in the 6th century BC.

In any case, Dougga was an early and significant human settlement. The city’s urban character is evidenced by the presence of a necropolis with dolmens, the most ancient archaeological find at Dougga, a sanctuary dedicated to Ba’al Hammon, neo-Punic steles, a mau Even though our knowledge of the city before the Roman conquest remains limited, recent archaeological finds have revolutionized the image that we had of this period.

The identification of the temple dedicated to Masinissa beneath the forum disproved Louis Poinssot’s hypothesis that the Numidian city existed on the plateau, yet was distinct from the contemporary Roman settlement. The temple, which was erected in the tenth year of Micipsa’s reign (139 BC), is 14 meters wide and 6.3 meters long. It proves that the area around the forum was already built upon before the arrival of the Roman colonists. A building dating from the 2nd century BC has also been discovered nearby. Similarly, Dougga’s Mausoleum is not isolated, but is located within an urban necropolis.

Recent discoveries have disproved earlier theories about the so-called numidian walls. The walls surrounding Dougga are, in fact, not Numidian; they are part of the city’s fortifications, which were erected in late antiquity. Targeted excavations have also demonstrated that what had been interpreted as two Numidian towers within the walls were in fact two funeral monuments from the Numidian era that were subsequently repurposed as foundations and a section of defenses.

The discovery of Libyan and Punic inscriptions at the site sparked a debate about the administration of the city during the Kingdom of Numidia. During the Numidian period, local Berber institutions distinct from any form of Punic authority emerged. However, Camps observes that Punic shofets remained in place in several cities, including Dougga, during the Roman era. This indicates the persistence of Punic influence and the preservation of certain elements of Punic civilization long after the fall of the city.

The Roman Empire was founded.

Dougga Theater is the Dougga Theater.

Ruins amidst the olive trees of Dougga.

Following their conquest of the region, the Romans granted Dougga the status of an indigenous city.

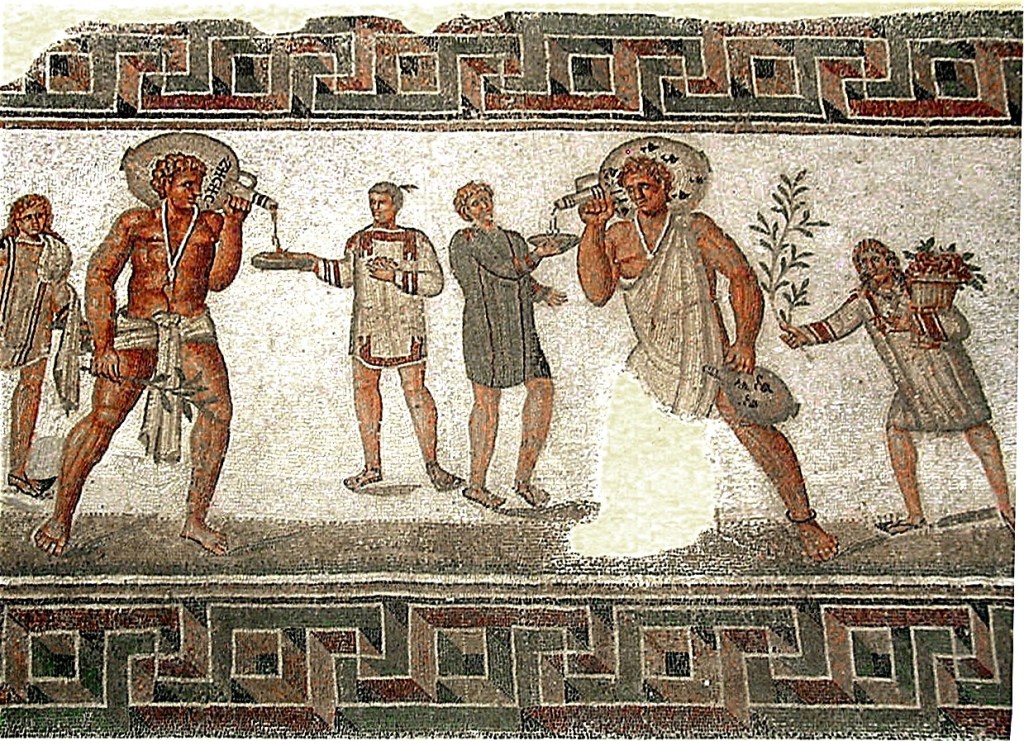

The establishment of the colony of Carthage during the reign of Augustus posed a challenge to Dougga’s institutional status. The city was included in the territory of the Roman colony, but around this time, a community of Roman colonists also arose alongside the existing settlement. For two centuries, the site was governed by two civic and institutional entities, namely the city with its peregrini and the pagus with its Roman citizens. Both cities had Roman civic institutions, including magistrates and a council (ordo) of decurions for the city, a local council from the end of the 1st century AD, and local administrators for the pagus, who were legally subordinated to the distant but powerful colony of Carthage. Furthermore, epigraphic evidence indicates that a Punic-style dual magistracy, the Sufetes, achieved civic status here well into the imperial period. In fact, the city once had three magistrates serving at once, a rarity in the Mediterranean.

Over time, the romanization of the city brought the two cities closer together. Notable members of the Peregrini progressively adopted Roman culture and conduct, became Roman citizens, and the councils of the two communities began to deliberate in unison. The increasing proximity of the communities was initially facilitated by their geographic proximity—there was no physical distinction between their two settlements—and later by institutional arrangements. During the reign of Marcus Aurelius, the city was granted Roman law, and the city’s inhabitants were automatically granted Roman citizenship. During the same period, the pagus was granted a certain degree of autonomy from Carthage, and was able to receive bequests and administer public funds.

Nevertheless, it was not until AD 205, during the reign of Septimius Severus, that the two communities came together as one municipality (municipium) and Carthage’s pertica was reduced. The city was supported by the euergetism of its great families of wealthy individuals, which sometimes reached exorbitant levels. Its interests were successfully represented by appeals to the emperors. Douggas development culminated during the reign of Gallienus, when it was granted the status of a separate Roman colony.

Douggas monuments attest to its prosperity from the reign of Diocletian to that of Theodosius I, but it fell into a sort of stupor from the 4th century. The city appears to have experienced an initial decline, as evidenced by the comparatively insufficient remains of Christianity. During the Byzantine period, the vicinity of the forum was transformed into a fortress, and several significant structures were demolished to furnish the necessary materials for its construction.

It was a caliphate.

Dougga was never completely abandoned following the Muslim invasions of the area. For a long time, Dougga remained the site of a small village populated by the descendants of the city’s former inhabitants, as evidenced by the small mosque situated in the Temple of August Piety and the small bath dating to the Aghlabid period on the southern flank of the forum.

Archaeological work

The first Western visitors to have left eyewitness accounts of the ruins reached the site in the 17th century. This trend continued in the 18th century and at the start of the 19th century. The best-preserved monuments, including the mausoleum, were described and, at the end of this period, were the object of architectural studies.

Archaeological work has influenced archaeological work.

The first Western visitors to leave eyewitness accounts of the ruins reached the site in the 17th century. At the end of the 18th century, the best-preserved monuments, including the mausoleum, were described.

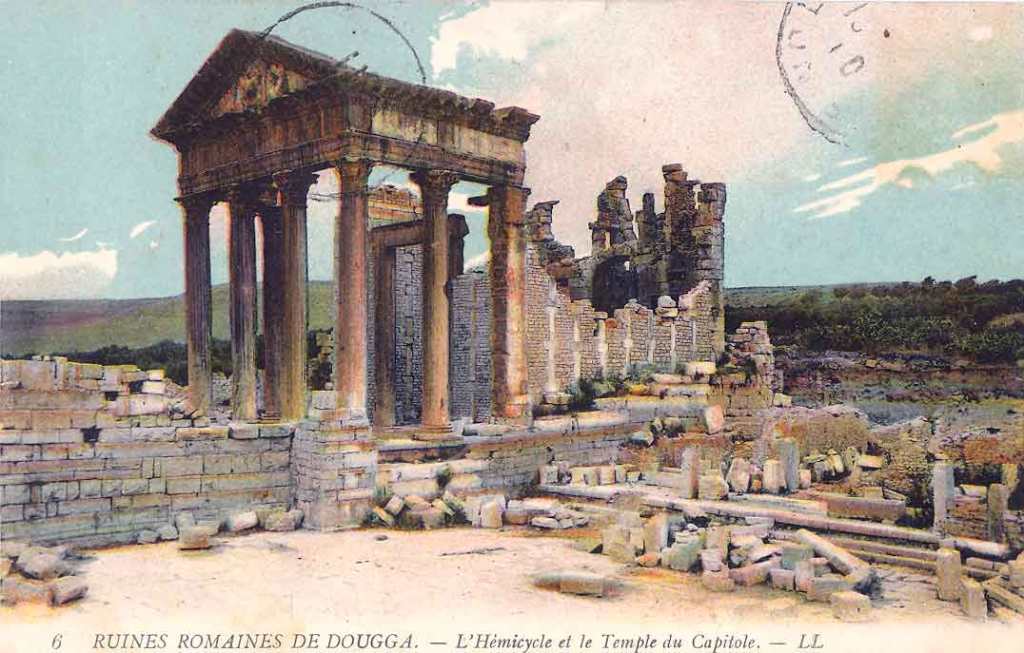

The establishment of France’s Tunisian protectorate in 1881 led to the creation of a national antiquities institute, for which the excavation of the site at Dougga was a priority from 1901, parallel to the work carried out at Carthage. The initial focus of the excavations at Dougga was on the vicinity of the forum; subsequent discoveries ensured a consistent pattern of excavations at the site until 1939. In addition to these excavations, work was undertaken to restore the capitol, of which only the front and base of the wall of the cella were still standing, and to restore the mausoleum, particularly between 1908 and 1910.

Subsequent to Tunisia’s declaration of independence, additional structures were excavated, including the Temple of Caracalla’s Victory in Germany. During the same period, the final inhabitants of the site were expelled and relocated to a village situated on the plain a few kilometers away from the antique site, referred to as New Dougga. In 1991, the decision was taken to transform the site into a national archaeological park. A cooperative scientific program aims to promote the study of the inscriptions at the site and the pagan temples. Dougga was added to the UNESCO list of world heritage sites in 1997.

Despite its significance and exceptional condition, Dougga remains undiscovered by many tourists and receives a mere 50,000 visitors annually. The construction of an on-site museum is currently under consideration, while the national antiquities institute has established a website that showcases the site and the surrounding region. At present, visitors with sufficient time can appreciate Dougga, not only for its numerous ruins but also for its olive groves, which lend the site a distinct ambience.

Dougga’s “Liberty” was Dougga’s “Liberty.”

Inscription in honor of Marcius Maximus, which was erected jointly by the pagus and the civitas.

From AD 205, when the city (civitas) and community (pagus) fused into one municipality, Dougga bore the title liberum, whose significance is not immediately clear. According to Merlin and Poinssot, the term comes from the name of the god Liber, in honor of whom a temple was erected at Dougga. The Thibursicum Bure constitutes an exception to the general rule, as the titles of the other municipia, including the term liberum, do not incorporate the names of any divinities. Therefore, this hypothesis has been abandoned. Alternatively, liberum may be construed as a reference to a free status (libertas, “liberty”) This interpretation is supported by an inscription found at Dougga that honors Alexander Severus as the “preserver of liberty.”

However, it is not clear exactly what form this liberty took. Toutain is of the opinion that this designation pertains to a specific type of municipium, i.e., free cities where the Roman governor lacked the authority to oversee the municipal magistrates. Nonetheless, there is no evidence to suggest that Dougga possessed exceptional legal privileges akin to those associated with certain free cities, such as Aphrodisias in Asia Minor. Veyne has thus suggested that Dougga’s “freedom” is nothing but an expression of the concept of liberty without any legal meaning; obtaining the status of a municipium had freed the city of its subjugation and enabled it to adorn itself with the “ornaments of liberty” (ornamenta libertatis). The city’s liberty was celebrated just as its dignity was extolled; the emperor Probus is a “preserver of liberty and dignity” (conservator libertatis et dignitatis). Gascou, in line with Veyne’s interpretation, describes the situation thus: “Liberum, in Thugga’s title, is a term […] with which the city, which had waited a long time for the status of a municipium, is happy to flatter itself”.

The civitas erected an inscription shortly before the fusion with the pagus. This inscription is the only record we have of the city’s institutions.

Despite Gascous conclusion, recent efforts have been made to identify concrete aspects of Dougga liberty. Lepelley believes that this must be a reference to the relations between the city and Rome and that the term can cover a range of diverse privileges of differing degrees. The liberty of the municipia established during the reign of Septimius Severus could thus be interpreted as a reference to the fiscal immunity facilitated by the immense wealth of the region and the emperor’s generousness towards each municipium during its fusion. During the reign of Gallienus, a certain individual in Dougga, Aulus Vitellius Felix Honoratus, made an appeal to the emperor “to guarantee the public liberty”. Lepelley believes that this is an indication that the city’s privilege had been questioned, despite Dougga’s ability to preserve its concessions, as evidenced by an inscription to the honor of “Probus, the defender of its liberty.”

According to Christol, this interpretation overly restricts the meaning of the word libertas. In Christol’s view, it is important not to forget that the emperor’s decision in 205 must have been taken in response to a request made by the emperor. During the reign of Marcus Aurelius, the civitas had achieved autonomy, which would have caused a certain degree of unease in the pagus. The inhabitants of the pagus would have expressed concern or even refusal when faced with the pretensions of their closest neighbors. This would explain the honor that the pagus attributed to Commodus.

For Christol, the term liberum must be understood both in this context and in an abstract sense. This liberty derives from belonging to a city and expresses the end of the civitas’ dependence. It also serves to placate the fears of the inhabitants of the pagus, and opens the door to a later promotion to the status of a colony. This promotion occurred in AD 261, during the reign of Gallienus, following an appeal from Aulus Vitellius Felix Honoratus in Christol’s version of events. Christol also points out that, despite the abstract nature of terms such as libertas or dignitas, their formal appearance should refer to concrete and unique events.

Leave a comment