Dingle (Irish: An Daingean or Daingean Uí Chúis, meaning “fort of Ó Cúis”)is a town in County Kerry, Ireland. The only town on the Dingle Peninsula, it sits on the Atlanticcoast, about 50 kilometres (30 mi) southwest of Tralee and 71 kilometres (40 mi) northwest of Killarney.

A large number of Oghamstones were set up in an enclosure in the 4th and 5th centuries AD at Ballintaggart.

The town developed as a port following the Norman invasion of Ireland. By the thirteenth century, more goods were being exported through Dingle than Limerick, and in 1257 an ordinance of King Henry III imposed customs on the port’s exports. By the fourteenth century, importing wine was a major business. The 1st Earl of Desmond, who held palatine powers in the area, imposed a tax on this activity around 1329. By the sixteenth century, Dingle was one of Ireland’s main trading ports, exporting fish and hides and importing wines from the continent of Europe. French and Spanish fishing fleets used the town as a base.

Connections with Spain were particularly strong, and in 1529 The 11th Earl of Desmond and the ambassador of Emperor Charles V signed the Treaty of Dingle. Dingle was also a major embarkation port for pilgrims to travel to the shrine of Saint James at Santiago de Compostela. The parish church was rebuilt in the sixteenth century under “Spanish patronage” and dedicated to the saint.

In 1569 the commerce of the town was increased when it was listed as one of fifteen towns or cities which were to have a monopoly on the import of wine.

Second Desmond Rebellion

The Dingle Peninsula was the scene of much of the military activity of 1579–80. On 17 July 1579 James FitzMaurice FitzGerald brought a small fleet of ships to Dingle. He made landfall, launching the Second Desmond Rebellion, but was to die soon after in a minor skirmish with the forces of a cousin. The fleet left the town after three days, anchoring at Dún an Óir at the western end of the peninsula, leading eventually to the Siege of Smerwick of 1580.

Walled town and chartered borough

The residents of Dingle applied in 1569 for a “murage grant” to construct wallsaround the town. The grant was not forthcoming on that occasion. Following the defeat of the Desmond Rebellion, Queen Elizabethdirected that a royal charterbe granted to incorporate the town as a borough, and to allow for the construction of walls. Traces of these town walls can still be seen, while the street layout preserves the pattern of burgage plots.

Although Elizabeth intended to grant a charter, the document was only obtained in 1607. On 2 March of that year her successor, James I, sealed the charter, although the borough and its corporation had already been in existence for twenty-two years. The head of the corporation was the sovereign, fulfilling the role of a mayor. In addition to the sovereign, who was elected annually on the Feast of St Michael, the corporation consisted of twelve burgesses. The area of jurisdiction of the corporation was all land and sea within two Irish miles of the parish church. The borough also had admiralty jurisdiction over Dingle, Ventry, Smerwick and Ferriter’s Creek “as far as an arrow would fly”.

The charter also created Dingle a parliamentary borough, or constituency, electing two members to the House of Commons of the Irish Parliament.

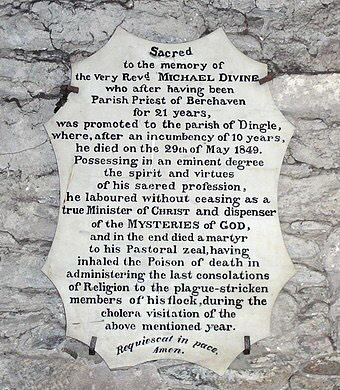

Dingle suffered greatly in the Nine Years’ War and the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, being burnt or sacked on a number of occasions. The town started to recover in the eighteenth century, due to the efforts of the Fitzgerald family, Knights of Kerry, who established themselves at “The Grove” at this time. Robert Fitzgerald imported flax seed and by 1755 a flourishing linen industry had been established, with cloth worth £60,000 produced annually. The trade collapsed following the industrialproduction of cotton in Great Britain, and was virtually extinct by 1837. The town fell victim to a cholera plague in 1849.

County Kerry (Irish: Contae Chiarraí) is a county in Ireland. It is in the Southern Region and the province of Munster. It is named after the Ciarraige who lived in part of the present county. The population of the county was 155,258 at the 2022 census.A popular tourist destination, Kerry’s geography is defined by the MacGillycuddy’s Reeksmountains, the Dingle, Iveraghand Beara peninsulas, and the Blasket and Skellig islands. It is bordered by County Limerick to the north-east and Cork County to the south and south-east.

Kerry (Irish: Ciarraí or in the original old-Irish language reform spelling Ciarraighe) means the “people of Ciar” which was the name of the Gaelic tribe who lived in part of the present county. The legendary founder of the tribe was Ciar, son of Fergus mac Róich. In Old Irish “Ciar” meant black or dark brown, and the word continues in use in modern Irish as an adjective describing a dark complexion. The suffix raighe, meaning people/tribe, is found in various -ry place names in Ireland, such as Osry—Osraighe Deer-People/Tribe. The county’s nickname is the Kingdom.

Lordship of Ireland

On 27 August 1329, by Letters Patent, Maurice FitzGerald, 1st Earl of Desmond was confirmed in the feudal seniority of the entire county palatine of Kerry, to him and his heirs male, to hold of the Crown by the service of one knight’s fee. In the 15th century, the majority of the area now known as County Kerry was still part of the County Desmond, the west Munster seat of the Earl of Desmond, a branch of the Hiberno-Norman FitzGerald dynasty, known as the Geraldines.

Kingdom of Ireland

In 1580, during the Second Desmond Rebellion, one of the most infamous massacres of the Sixteenth century, the Siege of Smerwick, took place at Dún an Óir near Ard na Caithne (Smerwick) at the tip of the Dingle Peninsula. The 600-strong Italian, Spanish and Irish papal invasion forceof James Fitzmaurice Fitzgerald was besieged by the English forces and massacred.

In 1588, when the fleet of the Spanish Armada in Irelandwere returning to Spainduring stormy weather, many of its ships sought shelter at the Blasket Islands and some were wrecked.

During the Nine Years’ War, Kerry was again the scene of conflict, as the O’Sullivan Beare clan joined the rebellion. In 1602 their castle at Dunboy was besieged and taken by English troops. Donal O’Sullivan Beare, in an effort to escape English retribution and to reach his allies in Ulster, marched all the clan’s members and dependants to the north of Ireland. Due to harassment by hostile forces and freezing weather, very few of the 1,000 O’Sullivans who set out reached their destination.

In the aftermath of the War, much of the native owned land in Kerry was confiscated and given to English settlers or ‘planters’. The head of the MacCarthy Mor family, Florence MacCarthy was imprisoned in London and his lands were divided between his relatives and colonists from England, such as the Browne family.

In the 1640s Kerry was engulfed by the Irish Rebellion of 1641, an attempt by Irish Catholics to take power in the Protestant Kingdom of Ireland. The rebellion in Kerry was led by Donagh McCarthy, 1st Viscount Muskerry. His son the Earl of Clancarty held the county during the subsequent Irish Confederate Wars and his forces were among the last to surrender to the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland in 1652. The last stronghold to fall was Ross Castle, near Killarney.

The Famine

In the 18th and 19th centuries Kerry became increasingly populated by poor tenant farmers, who came to rely on the potato as their main food source. As a result, when the potato crop failed in 1845, Kerry was very hard hit by the Great Irish Famine of 1845–49. In the wake of the famine, many thousands of poor farmers emigrated to seek a better life in America and elsewhere. Kerry was to remain a source of emigration until recent times (up to the 1980s). Another long term consequence of the famine was the Land War of the 1870s and 1880s, in which tenant farmers agitated, sometimes violently, for better terms from their landlords.

War of Independence and Civil War

In the 20th century, Kerry was one of the counties most affected by the Irish War of Independence (1919–21) and Irish Civil War (1922–23). In the war of Independence, the Irish Republican Army fought a guerilla war against the Royal Irish Constabulary, and British military. One of the more prominent incidents in the conflict in Kerry was the siege of Tralee in November 1920, when the Black and Tans placed Tralee under curfew for a week, burned many homes, and shot dead a number of local people in retaliation for the IRA killing of five local policemen the night before. Another was the Headford Junction ambush in spring 1921, when IRA units ambushed a train carrying British soldiers outside Killarney. About ten British soldiers, three civilians and two IRA men were killed in the ensuing gun battle. Violence between the IRA and the British was ended in July 1921, but nine men, four British soldiers and five IRA men, were killed in a shoot-out in Castleisland on the day of the truce itself, indicating the bitterness of the conflict in Kerry.

Following the Anglo-Irish Treaty, most of the Kerry IRA units opposed the settlement. One exception existed in Listowel where a pro-Treaty garrison was established by local Flying Column commandant Thomas Kennelly in February 1922. This unit consisted of 200 regular soldiers along with officers and NCOs. A batch of rifles, machine guns and a Crossley tender were sent from Dublin. Listowel would remain a base for those supporting the treaty throughout the conflict. The town was eventually overcome by superior numbers of anti-Treaty forces belonging to the Kerry No. 2 and 3 Brigades in June 1922. In the ensuing civil war between pro- and anti-treaty elements, Kerry was perhaps the worst affected area of Ireland. Initially the county was held by the Anti-Treaty IRA but it was taken for the Irish Free State after seaborne landings by National Army troops at Fenit, Tarbert and Kenmare in August 1922. Thereafter the county saw a bitter guerilla war between men who had been comrades only a year previously. The republicans, or “irregulars”, mounted a number of successful actions, for example attacking and briefly re-taking Kenmare in September 1922. In March 1923 Kerry saw a series of massacres of republican prisoners by National Armysoldiers, in reprisal for the ambush of their men—the most notorious being the killing of eight men with mines at Ballyseedy, near Tralee. The internecine conflict was brought to an end in May 1923 as the rule of law was re-established following the death of IRA Chief of Staff Liam Lynch, and the order by Frank Aiken to dump all arms.

The Lakes of Killarney are a scenic attraction located in Killarney National Park near Killarney, County Kerry, in Ireland. They consist of three lakes – Lough Leane, Muckross Lake (also called Middle Lake) and Upper Lake.

Lough Leane (from Irish Loch Léin ‘lake of learning’) is the largest and northernmost of the three lakes, approximately 19 square kilometres (4,700 acres) in size. It is also the largest body of fresh water in the region. The River Launedrains Lough Leane to the north-west towards Killorglinand into Dingle Bay.

Lough Leane is dotted with small forested islands, including Innisfallen, which holds the remains of the ruined Innisfallen Abbey. On the eastern edge of the lake, Ross Island, more properly a peninsula, was the site of some of the earliest Copper Age metalwork in prehistoric Ireland. Ross Castle, a 15th-century keep, sits on the eastern shore of the lake, north of the Ross Island peninsula.

Muckross Lake

Also known as Middle Lake or Torc Lake, Muckross is just south of Lough Leane. The two are separated by a small peninsula, crossed by a stone arched bridge called Brickeen Bridge. It is Ireland’s deepest lake, reaching to 75 metres (246 ft) in parts. A paved hiking trail of approximately 10 km (6.2 mi) circles the lake.

Upper Lake

The Upper Lake is the smallest of the three lakes, and the southernmost. It is separated from the others by a winding channel some 4 km (2.5 mi) long.