The fulgural art of the Etruscans.

The Etruscan discipline (the complex of Etruscan religious precepts) was also part of the interpretation of lightning and thunder. The teachings on the subject were attributed to the Nymph Vegoia and were transcribed in the so-called Libri Fulgurales.

No trace of the Etruscan texts remains, but some references and/or fragments of the same have merged into writings by classical authors such as Pliny the Elder (Natural History), Seneca (Natural Questions) and Giovanni Lido (On Celestial Signs).

Seneca specifies that the Etruscans were the most skilled in the interpretation of lightning and that according to the latter lightning were not natural events but manifestations of the will of the gods that could be interpreted.

To interpret the lightning it was necessary to identify the origin of the same, where they fell and where they returned (the Etruscans in fact believed that the lightning always bounced back).

According to the Etruscans, the sky was divided into sixteen sections, each presided over by a divinity, oriented according to the cardinal axes. By drawing two ideal lines in the north-south (Cardo) and east-west (Decumanus) directions, the sky was then divided into four quadrants of four sections each.

The deities positioned in the east (Pars Familiaris) were considered favorable, those in the west (Pars Hostilis) unfavorable.

Lightning could be launched from Tinia but also from eight other deities (including Uni, Menerva, Setlans, Maris and Satres). The father of the gods, however, unlike the others, had three types of lightning: the first warned (presagum), the second could have benevolent but also harmful effects (ostentarium), the third was destructive (peremptorium). Tinia could freely use the first lightning, for the launch of the second and third lightning she had to turn instead to the Consentes gods and the Involute gods. Each deity threw the thunderbolts from his seat into the sky, except Tinia who could send them from three zones.

For the purposes of correct interpretation it was not only important the origin of the lightning but also where it fell and therefore the sign was the most favorable when it came from the east and returned them.

According to the Etruscans, lightning as well as from the sky could also come from the ground (underworld), the former had an oblique trend, the latter straight.

The Etruscan discipline from the classification point of view was very detailed and identified at least forty different types of lightning for appearance, colors and effects.

With regard to the meaning, lightning could be of three kinds: the first (before the act) advises or not to perform an action that has been thought, the second confirms whether an event (accomplished) should have positive or negative consequences, the third warns about a danger to be avoided.

By observing certain rites and invocations it was possible to condition or even obtain lightning.

At the end of the interpretation of the lightning was put in place the ceremony of burial of the lightning and purification of the place. The burnt remains were collected in a well that was sealed and fenced. The ritual also included the sacrifice of an animal and the place could no longer be trampled on.

With regard to the interpretation of thunder we can consult the brontoscopic calendar transcribed by Giovanni Lido in the Liber De Ostientis (late sixth century BC) which made use of a Latin translation of the same made by Nigidio Figulo probably on the basis of an Etruscan text. It is a sort of list of predictions depending on the day the thunder was heard.

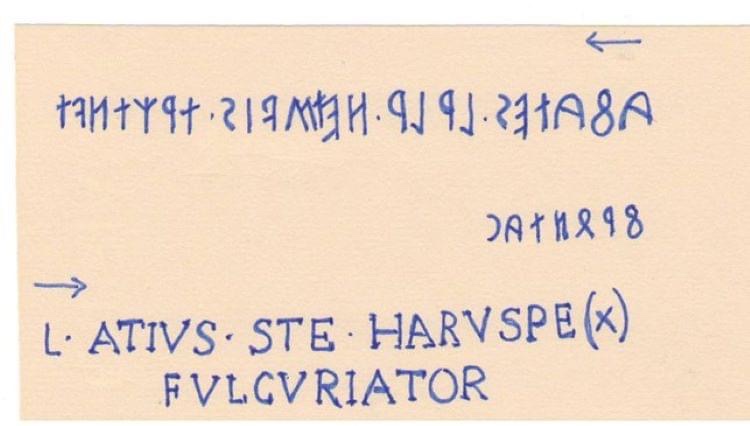

For completeness it should be noted that thanks to the text of a bilingual Etruscan Latin of Pesaro – “Laris Cafatius Larisis Filius Stellatina haruspe(x) fulguriator” = Laris Cafatio son of Laris of the (tribe) Stellatina haruspice/interpreter of lightning); “Cafates netśvis trutnvt frontac” = (Laris Cafatio (son) of laris haruspice and fulgural interpreter -, we know that the Etruscan name of the priest who interpreted lightning was frontac.

On Etruscan fulgural art see, among others, Adriano Maggiani in Gli Etruschi una nuova immagine, Giunti, 1984, pages 146 et seq.; Giovannangelo Camporeale, Gli Etruschi Storia e civiltà, Quarta edizione, UTET, 2015, pag. 166 – 167; Maurizio Martinelli, Gli etruschi Magia e Religione, Convivio, 1992, pagg. 102 et seq., Andrea Verdecchia, Mitologia etrusca, Effigi, 2022, pagg. 43 et seq.

Below are images of bronze of Tinia intent on throwing a lightning datable to the VI – V century BC at the Cleveland Museum and of the bilingual inscription of Pesaro.